A dental picture that’s worth thousands of dollars—literally

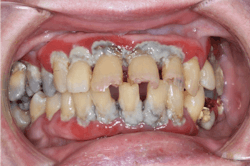

Take a look at the two rows of pictures below. They are of the same teeth. Can you tell a difference? Aside from the hue, which we all know is easily modified, they are essentially equivalent. The major difference that you may take most interest in is this: the photos on the top line are literally worth thousands of dollars—around $3,500 to be exact—while the bottom row of photos cost less than $200. The discrepancy is mind-blowing, and yet there are many of us, me included, who have fallen victim to the perception and well-played marketing paradigm that the best is always the most expensive. Let’s expand on this concept as it pertains to intraoral cameras.

When I started up practice, naiveté was my middle name. If the dental supply representative said I needed a, b, and c, I bought them without question. Blame that on whatever you’d like, but I’ll submit I was so focused on getting patients in the door and offering the “best of the best,” I perhaps gained comfort knowing I could refer to the “dental supply and equipment specialists” when it came to equipping my office. Intraoral cameras were no exception.

Fast-forward to today, and experience, trial, and error have taught me a thing or two along the way to becoming a savvier dental consumer and small-business owner. The repeated use of my “name-brand” cameras necessitated an investment in new devices. Price comparisons for intraoral cameras ranged from $50 to $5,000. I was a bit baffled that something so simple, with a USB port and small lens, could have so much of a price range. The technology, in pragmatic reality, was not technical enough to justify this divergence. So I decided to give it a go and purchase a $200 camera that came with many favorable reviews and was supposedly easily integrated into my software system (Eaglesoft). I didn’t want a lot of hassle or headache. I reasoned that if the camera worked well, then I could equip my eight operatories for less than it would cost to buy one “name-brand” camera. If I didn’t like it, I could send it back. The result is what you see in the bottom row of photos, which easily suffice for their intended purposes: basic record-keeping, patient education, diagnoses, and insurance claims. In addition, there is clearly enough detail to see things up close that may not be reflected in the mirror or seen with the naked eye, which saves money and teeth in the long run. Moreover, the setup and integration time into my software was approximately 10 to 15 minutes.

Skeptical? Too good to be true? I get it. I was too. I’ll argue, though, that investing in your practice can only grow your capacity to operate as a business and clinical provider. Would it not be prudent then to ask what you’re using your intraoral photos for? Are they for record-keeping, insurance claims, comparisons, before-and-afters, patient education? Do you want warranties, technical support, and seamless integration? How many cameras do you need? How often do you use them? Answering these questions will help direct your research and subsequent budget for these purchases.

While the majority of my photos are taken with the intraoral camera, I use a Canon EOS Rebel T3i with a 100 mm macro lens and a rim light flash (see right) for large reconstruction cases or full-mouth captures. This package cost me just under $2,000, which is surprisingly less than what the dental supplier wanted for a new intraoral camera! Yup. Really. When I was in a bind, before I purchased additional intraoral cameras, I even whipped out my old iPhone 7—which actually took a pretty decent picture of a crack I wanted to document on no. 18 (see below). Try to convince me now I need that really expensive intraoral camera!As an adjunct in the clinical setting, intraoral cameras are invaluable. When you put a picture in front of patients and have them diagnose their own problems, the next question is usually, “How soon can I get in to get it fixed?” Furthermore, these photos are vital for insurance claims processing, as clinical proof of what we do (or don’t do) is increasingly becoming mandatory. If you don’t have or use intraoral cameras on a daily basis, start doing it now. Lastly, I would not be vigilant in this discussion if I failed to mention that these photos can be decisive factors in litigation cases, which is unfortunate but true.

What’s my point? We are capable of being smart and thrifty with many types of purchases while not being held hostage to dental supply companies, intraoral cameras included. I don’t think you need convincing that these cameras are a valuable asset to your practice. That is not breaking news, but what you perhaps haven’t realized is that there are tremendous savings available to purchase new cameras if you’re a first-time buyer or, like me, you need replacement and/or additional cameras. This opens the door for us to invest in things that assist us in more effective patient care while generating production and savings in tandem (e.g., lasers, scanners, printers, etc.).

What all this essentially means is that Amazon, Costco, and third-party suppliers who offer the same materials at a fraction of the cost have infiltrated the dental market with healthy competition to our advantage. If you spin it all correctly, your pictures from your intraoral cameras can be “worth” hundreds of dollars and be a generator of thousands. I’ll take that to the bank any day.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Breakthrough Clinical, a clinical specialties newsletter from Dental Economics and DentistryIQ. For more information or to subscribe, visit dentistryiq.com/subscribe.

Stacey L. Gividen, DDS, a graduate of Marquette University School of Dentistry, is in private practice in Hamilton, Montana. She is a guest lecturer at the University of Montana in the Anatomy and Physiology Department. Dr. Gividen is the editorial director of Endeavor Business Media’s clinical dental specialties e-newsletter, Breakthrough Clinical, and a contributing author for DentistryIQ, Perio-Implant Advisory, and Dental Economics. She also serves on the Dental Economics editorial advisory board. You may contact her at [email protected].