Q:

It seems like every daythere is some new type of crown entering the market. New technologies abound for this area of dentistry, and the advertising always claims superior results with each new procedure or technology. I am quite confused about what to do for my patients. Are these new materials and technological concepts actually better, and should I be incorporating them into my practice? The cost of producing dentistry is constantly increasing, which makes the decision to change procedures and equipment more difficult. What do you suggest?

A:

I receive questions like yours very often while I am providing continuing education courses. Yes, the cost of doing dental preventive and treatment procedures is increasing constantly, third-party payment is decreasing in many states, and the revenue for your services is not increasing proportionately to compensate for these changes. Statistics from the American Dental Association show that dentists' net revenue is at the same level it was about 20 years ago. All of these factors make your questions more important. Which new concepts, techniques, and materials are potentially the most valuable, and which ones should you incorporate into your practice?

ALSO BY DR. GORDON CHRISTENSEN | Pulp cap or endo?

Since you asked about fixed prosthodontics (crowns and bridges), I will limit my comments to that area of dentistry. Undoubtedly you know that crowns are the largest part of a typical general dentist's practice revenue, accounting for about one-third to more than one-half of all income for an average general practice. Additionally, eight or nine crowns out of 10 are accomplished as singles-not quadrants, full arches, or full-mouth rehabilitations-which indicates a reduction from the past.

Historically, crowns have been among the most lifelike and long-lasting of all oral treatment. Properly fabricated and seated crowns often will serve for decades, with some even lasting a lifetime. Most patients forget that the crowns are in place, compared to some dental treatment that occasionally requires retreatment or repair.

I have some suggestions, so please analyze my comments to see if change is in order for your practice:

1. Are you satisfied with the clinical longevity of the fixed prosthodontics you provide for your patients? Porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) crowns have been the predominant crown and bridge procedure in dentistry for nearly 60 years. They are well-proven, viable restorations. Their clinical longevity varies depending on many factors such as occlusion, diet, oral hygiene, and quality of the original fabrication. However, most PFM crowns are still serving well at 20 years (figure 1).

Figure 1: PFM crowns properly fabricated and cemented can serve for many years.

Gold alloy crowns, now nearly extinct, serve for up to 40 years or more, but because of the metal display, patients seldom accept them anymore. Dentists, however, know their long-term value.

Will full-zirconia crowns challenge the historical crowns relative to longevity? Nobody knows. Our research at Clinicians Report Foundation shows that full-zirconia crowns made with proven zirconia products have the potential for long-term service (figures 2-4). Almost all US general dentists use full-zirconia crowns at least some of the time.

This is a logical decision. Be wary at least for a while with the "esthetic" zirconia crowns; they need additional long-term research. This modified form of zirconia has reduced strength and other less desirable physical properties compared to full zirconia.

If you are satisfied with the longevity of your PFM or gold-alloy crowns, continue using these materials, but also include full zirconia, especially for patients for whom they've served acceptably in the past.

Figures 2-4: Full-zirconia restorations are currently dominating single-crown use. Although serving well clinically for more than six years, the esthetic result could be somewhat better.

2. Are you satisfied with the esthetic characteristics of your fixed prosthodontic service?

PFM crowns serve well functionally, but many of them lighten due to the superficial stains wearing off. Conversely, if the stains have been fired onto the ceramic at a temperature that allows proper integration with the ceramic veneer, they can serve for many years. Unfortunately, laboratory competency with PFM is diminishing due to the increasing dominance of milling crowns in laboratories.

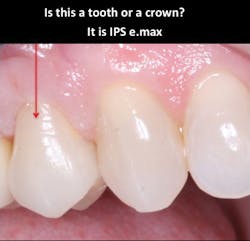

Lithium disilicate crowns, introduced about 10 years ago and in popular use for nearly that length of time, are now the major crown type for clinical situations requiring optimum esthetics. These are the most beautiful all-ceramic crowns in the history of dentistry, and their moderate strength allows them to serve very well in both anterior and posterior tooth situations (figures 5 and 6). These crowns have limitations, however, when it comes to patients who are bruxers. Full-zirconia is probably a better choice for these patients in the posterior area of the mouth.

Figures 5 and 6: IPS e.max properly fabricated and seated is nearly impossible to differentiate from natural teeth.

Though only used successfully for a few short years, both full-zirconia and lithium disilicate crowns have astounding acceptance by the profession and patients, and their clinical service record is admirable. I do not see any reason why these types of crowns should not be two of the most commonly used restorations in most practices.

3. Are you satisfied with the way crowns are fabricated for your patients?

There are three ways crowns are currently made:

1. Prep, make conventional impression, physically send

impression to lab, technician makes crown, seat crown on

later appointment (figure 7).

2. Prep, scan impression, send impression to lab by e-mail,

technician makes crown, seat crown later or same day if laboratory is close to you.

3. Prep, scan impression, mill in office, seat crown on the same appointment.

No one option is better than the rest; all three options work very well. Method one is still the most commonly used method by more than 90% of dentists. Method two is growing rapidly as scanners become less expensive and easier to use. This concept is growing since some dentists do not want to be involved with the construction of the crown. Many prefer to use a laboratory to accomplish that part of the technique. Method three has now been available for more than 30 years and is used by about 10% of dentists, most of whom (and their patients) like the one-day crown procedure. I predict that method two will probably dominate the profession over the next several years.

Is one of these techniques best for you? If one way were profoundly better than the others, I could recommend it to you. However, I personally use all three options, depending on each individual patient's specific needs. Only you can decide, since the methods are essentially equal in their ability to serve your patients.

Figure 7: Conventional elastomer impressions still dominate crown and bridge procedures, but use of scanners is increasing rapidly.

Deciding when to change a technique, concept, or material

A few months ago, I was discussing the state of restorative procedures in the profession today compared to 50 years ago with a mature, experienced dentist. We agreed that there are many marvelous new concepts, materials, techniques, and technologies available now. The ability to treat many aspects of oral disease is much better than in the past. Dentists are significantly able to produce restorative dentistry that is far more esthetically pleasing. However, many of the procedures now being replaced were, in some ways, better. Don't throw all of them away. Some of the older restorative procedures are still very viable today. A few examples are gold alloy restorations, hemisecting teeth and restoring the remaining tooth segment, cantilever bridges where implants are not indicated, partial tooth restorations (inlays and onlays) instead of crowns, use of precision attachments/stress breakers that are currently not available in most ceramic restorations, and many others.

ALSO BY DR. GORDON CHRISTENSEN | Guided versus freehand dental implant placement

Summary

The many new products for fixed prosthodontic treatment that are available today make deciding where to spend discretionary practice dollars difficult. I suggest that practitioners analyze their crown and bridge services to determine if they are satisfied with the longevity and esthetics of their current procedures as well as how the crowns and bridges are being produced. These decisions will allow rational decisions to be made about whether to change the concepts as explained in this article.

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD, is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah. He is the founder and CEO of Practical Clinical Courses, an international continuing-education organization initiated in 1981 for dental professionals. Dr. Christensen is cofounder (with his wife, Dr. Rella Christensen) and CEO of Clinicians Report (formerly Clinical Research Associates).