After practicing general dentistry for many years, I have observed significant good innovations in dental procedures we can offer patients. However, I have also seen some procedures producing shorter service longevity for patients, higher cost per year of service, and more trauma for patients over time. What can be done to improve those procedures that are obviously inferior to older treatments?

I have had the opportunity to practice during the introduction and maturation of many new concepts into our profession. I agree with your question, and I have heard similar complaints from dentists, manufacturers, and patients.

Zirconia crowns in dentistry: Uses, clinical challenges, and solutions

Increase your service and revenue with elective dental procedures

About 40 years ago, there was an overt emphasis on esthetics, and I was one of the motivators of that movement. In my opinion, that emphasis has now been overdone. Of course, patients want esthetic procedures because they look better and feel better about themselves. But the result of the rush to esthetic dentistry has been reduced restoration longevity and less emphasis on preventive dentistry. Several other practice areas have also been pushed aside. Snow-white teeth, smiles, and esthetic procedures have become the major focus for many dental practices. The more important goal of tooth preservation has been neglected.

Using my experience in practice and research, this article includes my candid appraisal of only a few of the numerous procedures in dentistry that need to be improved and what can be done to improve them. I hope this information will be helpful, not only to you and other dentists but also to inventors, manufacturers, and distributors.

Resin-based composite restorations

It is common knowledge in dentistry that composite resin restorations have short longevity expectations. Most research shows that amalgam, although unesthetic and controversial, serves about twice as long as composite. Composite restorations and techniques to place them have been markedly improved since their introduction in the early 1960s. Early problems were high wear, surface roughness, postoperative tooth sensitivity, open contact areas, and inadequate curing. These challenges have been largely overcome. Why are composites still failing so soon?

A major negative factor is polymerization shrinkage, which is about 2%. Observe the wide-open margins and degeneration shown on these representative composite restorations (figure 1). Such open margins allow free access for microbes to the tooth preparation internally, and they encourage subsequent caries.

Potential solutions

- The shrinkage must be reduced or eliminated by manufacturers.

- Use a glass ionomer layer that has no dimensional change on setting under the composite (Equia Forte, Ketac Universal, or others).

- Disinfect the tooth preparation (Gluma, MicroPrime, or others).

- Reduce or eliminate bulk-fill restorations. Most of these products are adequate or good, but polymerization in deep restorations is poor in many cases due to inadequate use of light-curing.

- Continue development and use of long-term antimicrobial restorative materials that kill organisms on contact (Infinix).

Zirconia restorations

These restorations, introduced by Glidewell Laboratories more than a decade ago, have been one of the fastest-accepted concepts I have seen in my career. When used in their original formulations, zirconia restorations, as shown by Clinicians Report Foundation (CR), have had near-perfect clinical longevity over the 11 years they have been available. However, there are some clearly observed challenges that still need to be overcome, including esthetics, open margins, crowns coming off in service (figure 2), near impossibility of crown removal or recontouring, changed weaker formulations with other less-desirable physical characteristics, and the necessity to use external glaze to improve color.

Potential solutions

- Technicians and manufacturers are promoting some products without adequate clinical research. Clinicians are seeing failures related to this lack of research.

- Lab/clinician continuing education meetings should be held ASAP to mitigate this problem.

- Use resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) to cement zirconia crowns—not resin. CR has shown significantly less debonding with RMGI than resin (RelyX Luting Plus, FujiCEM Evolve, or others).

- Develop better rotary instruments to remove zirconia crowns.

- Employ research methods to improve the color of zirconia without placing glaze on it. Glaze wears opposing teeth and gradually wears off itself.

- Develop milling products that reduce the margin opening of current zirconia crowns.

- Use well-proven conventional procedures for patients where zirconia restorations appear to be questionable (gold alloy or conventional fixed or removable prostheses).

Implants

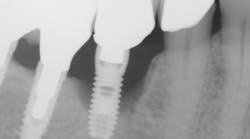

The current implant literature has many articles showing the development of peri-implantitis around implants after several years of service (figure 3). One of the major articles showed 45% of implants with some level of peri-implantitis after nine years of service.1 That has certainly been the case in my patients after 32 years of placing implants. Are implants always the first choice when saving a tooth that looks potentially problematic? No! Restoration of the tooth can often be better than an implant.

Potential solutions

- Inclusion of instruction on implant surgery and prosthodontics in predoctoral dental schools should be mandatory!

- Inclusion of implant maintenance should be mandatory in hygiene schools.

- Evaluate research and identify other metals, metal oxides, or other substances for implants, and implement those that could be better than titanium alloy as dental implants.

- Use well-proven conventional procedures for patients whose implants appear to be questionable (fixed or removable prostheses).

Endodontic failures

Properly accomplished endodontic procedures are highly successful. However, it is well-known among experienced practitioners that as patients become older, some endodontic procedures slowly begin to fail. Because some endodontically treated teeth are so successful, inexperienced dentists often elect to perform endodontics when other procedures could be better and serve patients longer. Endodontically treated teeth are well known to have reduced service longevity.2 In a study by Lempel et al., the success rate of composites in endodontically treated teeth was reduced by approximately 20%.

Potential solutions

- Don’t do endodontics unless absolutely necessary!

- Use pulp-capping procedures that are well proven to be successful if the pulp is vital.

- Use delicate, careful removal of caries in deep lesions. When dentin is hard to a spoon excavator, do not remove more tooth structure despite the color of the dentin.

- Place two one-minute applications of 5% glutaraldehyde and 35% HEMA solution to disinfect and desensitize the tooth.

- Place your choice of pulp-capping material (mineral trioxide aggregate, Ultradent MTA Flow, or others) followed by the restorative material of your choice.

Summary

Some newer dental materials, concepts, and technologies have been less successful than previously proven older techniques. What can we do to improve these frustrating procedures? Should we remain with the proven concepts? These four examples of procedures need to be improved.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the November 2022 print edition of Dental Economics magazine. Dentists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

1. Derks J, Schaller D, Håkansson J, Wennström JL, Tomasi C, Berglundh T. Effectiveness of implant therapy analyzed in a Swedish population: prevalence of peri-implantitis.

J Dent Res. 2016;95(1):43-49. doi:10.1177/0022034515608832

2. Lempel E, Lovász BV, Bihari E, et al. Long-term clinical evaluation of direct resin composite restorations in vital vs. endodontically treated posterior teeth—retrospective study up to 13 years. Dent Mater. 2019;35(9):1308-1318. doi:10.1016/j.dental.2019.06.002

Author’s note: The following educational materials from Practical Clinical Courses offer further resources on this topic for you and your staff.

One-hour videos:

- The New Glass Ionomers Really Work (Item #V3514)

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Failing Implants (Item #V2391)

Three-hour virtual classes:

- Christensen’s Most Frequent Failures and How to Avoid Them (Item #X4740)

- Making Occlusion Work for Your Practice (Item #X3145)

For more information, visit our website at pccdental.com or contact Practical Clinical Courses at (800) 223-6569.