Will the ADA find 2020 overhead to be 70% again?

For decades, the American Dental Association has measured average overhead for a general dentist at 70%. What do you think 2020’s will be with the two-month, COVID-induced sabbatical and associated personal protective equipment/COVID cost increases? Mathematically, that interruption should cause a 16% decrease in production in addition to the increased expenses that handled our profession’s “aerosolization.” Won’t overhead have to be above 80%?

If you want to think about life in time rather than overhead percentages, think about how 70% means we work three out of four days to cover expenses. We’d now have to work four out of five days to cover our new expenses. That would be 192 days for overhead and 48 days to use the remaining profit for our families, taxes, and retirement funds. We don’t know about you, but all the N-95-type expenses and up to 48 extra days of work to pay for them is not what any 60-plus-year-old dentists were planning on before that 0.13-micron virus changed everything! So, what can we do about it?

Become more efficient by working together

Many of us start as an associate (to get out of debt), go back into debt buying a practice, and then end a 40-year career by mentoring an associate to take over the practice and patients who are now friends. This path is based on what seems obvious: increased production happens when existing patients or an insurance company refers new patients.

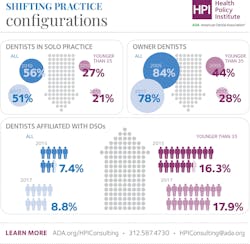

These days, most practices are in-network to attract young patients, and even though that dictates 40%–50% reduced fee collection (we know, shocker!), patients love to use their benefits. So, if we should share our practices to make them more efficient for profitability, what’s holding us back from doing so? The ADA Health Policy Institute states, “51% of dentists were solo practitioners in 2017, down from 65% in 1999” (figure 1). Are we getting better at sharing now that there are more women in the profession than men (figure 2)?

Dentistry used to be filled with introverted, engineer-type men who used 25- to 27-gauge needles that became dull with multiple uses (yes, they used to sterilize needles) while restoring teeth with silver (actually black) and gold restorations.

If it’s not male/female- or material-based decisions that make us not willing to share our practices with younger dentists, is it just “too complicated” to share our higher fee, out-of-network patients with someone else even though it lowers overhead? Or is it the patients who don’t want to be shared? Here’s a thought: maybe we need to pay the young associates like owners because the young in-network patients want a dentist who’s within 10 years of their age instead of 60 or older.

New patients = growth, but are young patients in-network?

How does a 30-something associate dentist with $100,000 in debt accumulate enough in-network collection to purchase a practice within five to 10 years for another $750,000? From an owner’s perspective, if 2020 saw 80% overhead, it may be scary to hire an associate who earns 25%–30% of their production and guarantee those earnings. How will an owner or associate figure out numbers that work no matter what virus invades?

Their employer-paid benefits plans are what drive today’s 20- to 50-year-olds to a dental office. The unfortunate reality of a new dentist looking for patients will be finding these patients from the contracted, in-network systems, which scares new dentists from starting a practice from scratch since they will be tied to fees that are reduced 40%–60% compared to out-of-network fees. So, how do we do this group dental practice thing so that everyone wins?

Mutual respect, that’s how!

Based on empirical observation and ADA data, the typical solo practitioner-owner has a 60-year-old-plus patient base that has decreased their dependence on dental insurance. While you are benefiting from patients without in-network benefits, why not bring in an associate who grows a younger practice to handle the in-network crowd, with one caveat: the owner-dentist must treat the associate like the owner they wish to become before they buy in.

Why not give the associate a higher percentage for that new-patient base that they will develop separately, instead of making them search other options such as dental service organizations or another solo practice ownership? If the typical DSO pays 20%–25% of production, why not beat that with 30%–33% of out-of-network patients and 40%–50% for the new dentist’s in-network patients since collection is guaranteed, albeit at a 40%–50% reduced rate? Why not back-fill your new-patient quotas while current patients age into out-of-network people who have more complicated diagnostic and treatment options?

John Wilde, DDS, simplifies group practice overhead in an October 2020 Dental Economics article. “Almost no changes to our physical plant were required, so expenses such as heating and cooling, phones, business insurance (not malpractice), and rent changed little. Our overhead percentage dropped from 65% to 58%, while production increased 54%. Changes were so numerous that it’s hard to determine a single figure for fixed overhead savings, but rent, utilities, and some insurances were cut into thirds.

“Many other expenses were reduced on a percentage, but not a total dollar basis. Two additional staff were added, but production per team member increased by 15%. Dentistry is what I do for a living, and I study my accountant’s profit and loss statement and our internally generated monitors carefully, but I’m a ‘net per hour’ guy. To me, the most significant positive of the group concept is that higher production combined with lower overhead yields more net dollars.”

Bottom line for overhead and dentists

Why not make a hybrid practice that will keep older patients happy that they can stay in the experienced owner’s practice? This is while the young dentist earns more money to buy your practice while building one that will sustain him or her long after the older dentist retires? Let’s mutate!

Steven A. LeBeau, DDS, FAGD, received his BS from the University of Notre Dame in 1981. Dr. LeBeau graduated from Georgetown University's School of Dentistry in 1985 and served as a clinical instructor in the department of fixed prosthodontics. While teaching, he was in private practice in McLean and intensely studying orthodontics/TMJ disorders throughout the country from 1985 through 1990. Dr. LeBeau serves as the restorative director for his local Seattle Study Club.

Jeena E. Devasia, DDS, FAGD, earned her BS from Virginia Commonwealth University with the distinction of summa cum laude and continued her education at the VCU School of Dentistry, graduating in 2015. Dr. Devasia started her dental journey as Dr. LeBeau’s intern out of high school and joined as his associate following dental school, returning to her hometown of McLean. Dr. Devasia serves as president-elect of the Virginia Academy of General Dentistry, ADA delegate, and holds board positions for the Virginia Dental Association and local dental society.