Early childhood caries, although completely preventable, are highly prevalent and continue to devastate the pediatric population, particularly those in disadvantaged groups.1 With caries incidence so high, restorative dentistry continues to be a mainstay of dental practices throughout the world.

Choices for direct restoration materials can seem overwhelming and confusing. There are a multitude of materials available, and each comes with its unique claim to be the best. Their attributes are endless: highest filled, most esthetic, best adaptation, greatest radiopacity, least amount of shrinkage, bioactive properties, strongest, most durable. The list goes on and on. What’s the end result? Bewildered dentists are confronted with a maze of materials, trying to determine which one is best suited to serve their patients and their practices.

The simple truth is that until recently, there have only been three categories of materials to use as direct filling material for any intracoronal restoration for pediatric patients:

- metal (amalgam)

- plastic (composite resins or compomers)

- glass (glass ionomers)

Each of these materials comes with recommendations, clinical indications, and inherent strengths and weaknesses. Metal in the form of amalgam has been used effectively in class I and class II restorations for more than 150 years. Within the last decade, however, the safety of amalgam has been questioned due to concerns about high mercury content.2 The use and popularity of amalgam restorations has declined steadily as a result of multiple factors—from parents concerned about the toxicity of mercury to the availability of more esthetic alternatives. With just a simple Google search, parents and patients alike can find numerous sites citing amalgam toxicity. Often when these parents are presented with concerns about mercury and amalgam, they request alternatives to amalgam restorations for their children.

The general demand for esthetic restorations has never been higher. Parents want white teeth for themselves and their children. The dental industry has responded by creating many versatile, strong, and beautiful materials, and there is widespread availability of many excellent composite resins. However, studies driving concerns over composite resin materials containing bisphenol A (BPA) and cytotoxic matrix monomers posing health risks and adverse biological reactions have made it to the forefront of internet searches.3,4 We truly are living in an era in which the sharing of information can take place within seconds. As a result, parents are more frequently requesting materials without BPA or monomers.

Finally, glass ionomer cements (GIC) and resin-modified glass ionomer cements (RMGIC), with their inherent fluoride content and rechargeability, are excellent choices, respectively, for class I and class II restorations in primary teeth.5 But the strength and esthetics of GIC and RMGIC over time are less than ideal. Selecting the right restorative material becomes challenging when parents are concerned about any of the aforementioned options.

A new class of material—referred to as nano-ORMOCERs (ORganically MOdified CERamics)—mirror the clinical applications and indications of conventional composites while exhibiting enhanced biocompatibility and physical properties.4 The nano-ORMOCER is a ceramic-based direct restorative material.

Case study

In this case, a W3 ivory rubber dam clamp is placed on tooth A to be restored with an intracoronal restoration. Adjacent tooth B will be restored with a prefabricated pediatric zirconia crown (NuSmile; figure 1). A Hedy rubber dam with a slot style is placed extending from tooth A to the mesial of tooth C.

Note that the intracoronal restoration is completed from start to finish prior to crown preparation and cementation. Preparation for the intracoronal restoration incorporates a mechanical retention in the form of a dovetail and slight undercut. Over time, any bruxism habits would wear away the top-most occlusal portion of the tooth, taking the adhesive and restorative material with it. In the primary dentition, conservative preparation is paramount and will ultimately determine the success or failure of the restoration. Care must be taken to leave enough remaining tooth structure and not undermine cusps or facial or lingual/palatal walls. Additionally, the location and size of the

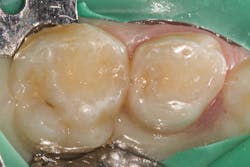

Once preparation and removal of the infected dentin is achieved, a sectional matrix and ring system (Composi-Tight 3D XR, Garrison Dental Solutions) is used. Taking particular care at the gingival margin, proper matrix placement will ensure control over leakage and any possible contamination, which is important for long-term success (figure 2).

A selective-etch technique with 35% phosphoric acid is used to achieve the highest possible bond strengths.6,7 The etchant is washed and the tooth is dried without desiccating it. A universal bonding agent (Futurabond U, Voco) is rubbed onto the tooth surface for 20 seconds (figure 3), and thenThis is a modified snowplow technique, in which the flowable base layer is light cured in combination with placement of 4 mm of the restorative material.8,9 This allows the flowable to extrude up to the occlusal surface and down to the gingival margins, filling any voids.

The restorative material is warmed first in a Caps Warmerrestoration is shown in Figure 8.

Nano-ORMOCER materials provide clinicians with an excellent restorative option for pediatric patients that can appease concerned caregivers without disrupting current workflows. No doubt public scrutiny of our restorative materials will continue, whether their conclusions are legitimate or ill-informed. But we will also continue to see children with dental caries, so we would do well to add new materials to our armamentarium that can support good oral health outcomes and reassure caregivers of their safety.

All photos courtesy of the author.

References

- Anil S, Anand PS. Early childhood caries: prevalence, risk factors, and prevention. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:157. doi:10.3389/fped.2017.00157

- Food and Drug Administration. US Department of Health and Human Services. Final Rule. Federal Register. Vol. 75, Issue 112. 21 CFR Part 872—Dental Devices. June 11, 2010. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2010-06-11/pdf/2010-14083.pdf

- Fleisch AF, Sheffield PE, Chinn C, Edelstein BL, Landrigan PJ. Bisphenol A and related compounds in dental materials. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):760-768. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2693

- Schubert A, Ziegler C, Bernhard A, Bürgers R, Miosge N. Cytotoxic effects to mouse and human gingival fibroblasts of a nanohybrid ormocer versus dimethacrylate-based composites. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(1):133-139. doi:10.1007/s00784-018-2419-9

- The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatric Restorative Dentistry. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 2019–2020:340-352. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_restorativedent.pdf?v=new

- de Oliveira da Rosa WL, Piva E, da Silva AF. Bond strength of universal adhesives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2015;43(7):765-776. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2015.04.003

- Lenzi TL, Guglielmi Cde AB, Umakoshi CB, Prócida Raggio DP. One-step self-etch adhesive bonding to pre-etched primary and permanent enamel. J Dent Child (Chic). 2013;80(2):57-61.

- Boksman L, Carson B, Santos GC. The continued evolution of class II matrix armamentarium. Oral Health. October 1, 2013. https://www.oralhealthgroup.com/features/the-continued-evolution-of-class-ii-matrix-armamentarium/

- Versluis A, Douglas WH, Cross M, Sakaguchi RL. Does an incremental filling technique reduce polymerization shrinkage stresses? J Dent Res. 1996;75(3):871-878. doi:10.1177/00220345960750030301

- Simonsen RJ. Preventive resin restorations: three-year results. J Am Dent Assoc. 1980;100(4):535-539. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1980.0125

- Mertz-Fairhurst EJ, Richards EE, Williams JE, et al. Sealed restorations: 5-year results. Am J Dent. 1992;5(1):5-10.