The deafening silence in dentistry

Dental professionals today have more personal protective equipment and regulations in the office space than ever before, yet one issue has continued to remain silenced—hearing loss. If hearing loss were officially considered a disability, it would rank as the highest disability class in the world.1 Currently, it ranks as the second highest work-related illness/injury, and in the United States, hearing issues have affected more than 25% of the population.2

Avoiding hearing loss

Dental clinicians can directly relate to and identify with colleagues who have lost significant amounts of hearing in one or both ears, yet what are we doing about it? As most of us accept graying hair due to aging, we, too, have accepted that our hearing will slowly fade as we age as a result of our profession. However, this thinking is flawed. Hearing loss—specifically noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL)—which plagues our industry, is 100% preventable.3

We have the option to protect one of our five senses from permanent and irreversible damage, but we are doing nothing about it. To our detriment, we have collectively chosen inaction, running contrary to our credo of being a preventive field. Despite decades of literature exposing our risk, and even recommendations by the American Dental Association itself, our governing and regulatory bodies have not taken a clear stance and pushed the use of hearing protection as the standard of care. This has left dental professionals exposed and at significant risk, and we all should be very concerned.

Compared to other health professionals, dentists have significantly worse hearing levels.4 This holds true for all ages, genders, and even when compared to the general population.5 NIHL causes permanent damage as early as 10–15 years upon exposure.6 Further, studies have shown our hearing capacity to be equivalent to people decades older than our age bracket.7

Dental professionals at risk

One of the biggest reasons NIHL affects us so directly is that hearing loss is a cumulative issue over time8; thus, while small exposures to damaging sounds for short periods may seem harmless at first, over time they do just as much damage as having a large firearm fired next to your ear.9 Think about it: we may spend only 25 minutes per patient in the chair using a high-speed handpiece, suction, and/or ultrasonics, but we do this multiple times each day, all week, and for an average career of 35 years. In fact, over the course of our careers, we spend more hours in the dental environment than anywhere else, and even when outside of the office, we readily engage in noise-rich activities. This accumulation of exposure slowly does its damage, and we do not notice the signs of permanent damage until it’s too late. Sound familiar? It should. We explain this same process to our patients when it comes to treating caries and infections, and we become frustrated when they ignore our diagnoses until they return with severe pain and swelling. Why aren’t we taking our own advice?

The damaging effects of noise go beyond the ear. Exposure to chronic high levels of noise can directly lead to significant systemic health issues, such as cardiovascular disease and depression.10 It reduces our productivity, increases stress, and interferes with communication and concentration. Our body’s response to this insult causes sympathetic and endocrine responses, which in turn affect our sleep patterns and ultimately follow a cascade that is a serious detriment to our overall health and well-being.11 Our best and easiest counter to this risk is prevention via utilization of hearing protection.

Contrary to my initial belief, the dental literature has warned us of the serious effects of NIHL for decades. In fact, the American Dental Association published as early as 1974 a recommendation of using hearing protection in the dental operatory, and since that time endless publications have pointed out the risks and also recommended hearing protection.12,13 Why have we ignored the warnings? For one, our options in the past were very limited.

Traditional foam ear plugs result in significant muffling of sounds and the inability to communicate with patients and staff. Studies show this as the number one reason hearing protection has been avoided.14 Even newer, high-tech solutions, such as noise-canceling headphones, are not practical for our environment as they are big, bulky, and, again, eliminate our ability to communicate. Passive protection plugs with filters were nice to try and definitely a step in the right direction, but the muffling and compromised communication persisted and didn’t provide what we needed, as all sounds are filtered whether or not they cause damage.

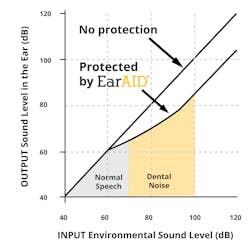

What we need is something small and lightweight that can both protect us from the damaging high decibel and frequency sound levels we are exposed to (figure 1), while simultaneously not affecting our ability to hear clearly and communicate with patients and staff. This technology simply never existed until recently, and is known as active hearing protection.15,16 Using a tiny electronic microchip, the high-level damaging sounds are instantly isolated and compressed to lower levels while still maintaining an open-ear response, resulting in 100% HD hearing (figure 2). Communication remains clear and unaffected, while hearing damage is prevented. With this new technology, we truly have a solution that will address all of our concerns and solve our noise-exposure issues.

I took it upon myself to create a solution: EarAID. As expected, it took me about a week to adjust to having something in my ears, not to mention the small echo and voice adjustment (known in the audiology world as the occlusion effect) that any plug will cause. Just like with loupes, once adjusted, it now feels like second nature.

It’s time we, as individual practitioners, take a stand and begin seriously addressing dentistry’s deafening silence. While we fret over the newest bonding agents and debate over impression materials and 3-D scanning tools, we continue to lose our hearing on a daily basis. Our governing bodies and dental associations can help take the lead in this cause by definitively stating that NIHL is an issue we need to take protective measures against as standard of care, but the final responsibility to take action is up to us. All new ideas will have their initial hesitations—just look at dental loupes before and loupes today—but nothing has the significant and permanent ramifications to our health that NIHL causes. Ultimately, it’s not a question of if, but rather, when and to what extent our hearing and quality of life will be affected by our profession.

Author’s disclosure: Dr. Shamardi has a financial interest/arrangement or affiliation with Forward Science, offering financial support or grant monies for or related to the content of this article.

Editor's note: This article was originally published in 2019 but has been updated as of December 2024.

References

1. Christensen J. Hearing loss an ‘invisible,’ and widely uninsured, problem. CNN website. https://www.cnn.com/2012/07/10/health/hearing-aid-insurance/index.html. Published July 2012. Updated September 12, 2016.

2. Themann CL, Suter AH, Stephenson MR. National research agenda for the prevention of occupational hearing loss—Part 1. Semin Hear. 2013;34(3):145-207.

3. Mathur NN. Roland PS. Meyer AD, ed. Noise-induced hearing loss clinical presentation. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/857813-clinical. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed August 30, 2019.

4. Ahmed NA, Ummar F, Girishraj, Sameer KM. Noise induced hearing loss in dental professionals: An audiometric analysis of dental professionals. J Dent Med Sci. 2013;11(3):29-31.

5. Lehto TU, Laurikainen ET, Aitasalo KJ, Pietilä TJ, Helenius HY, Johansson R. Hearing of dentists in the long run: A 15-year follow-up study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17(4):207-211.

6. Noise-induced hearing loss. American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. http://www.caohc.org/pdfs/ACOEM%20noise%20induced%20hearing%20loss.pdf. Published 2002. Accessed August 30, 2019.

7. Lazar A, Kauer R, Rowe D. Hearing difficulties among experienced dental hygienists: A survey. J Dent Hyg. 2015;89(6):378-383.

8. Theodoroff SM, Folmer RL. Hearing loss associated with long-term exposure to high-speed dental handpieces. Gen Dent. 2015;63(3):71-76.

9. Noise-induced hearing loss. National institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders website. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss#6. Updated May 31, 2019. Accessed August 30, 2019.

10. Serafni F, Biasi CSL, et al. Sound intensity and audiometric findings in the odontologic practice. Proceedings of the 30th Congress of the Neurotological and Equilibriometric Society; 2003.

11. Willershausen B, Callaway A, Wolf TG, et al. Hearing assessment in dental practitioners and other academic professionals from an urban setting. Head Face Med. 2014;10(1). doi:0.1186/1746-160X-10-1.

12. Noise control in the dental operatory. Council on Dental Materials and Devices. J Am Dent Assoc. 1974;89(6):1384-1385. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1974.0605.

13. Cooperman HN. Deafness to the dentist caused by high speed handpieces. Pak Dent Rev. 1965;15(3):108-110.

14. Reddy RK, Welch D, Thorne P, Ameratunga S. Hearing protection use in manufacturing workers: a qualitative study. Noise Health. 2012;14(59):202-209. doi:10.4103/1463-1741.99896.

15. Clinician’s perspectives on hearing protection devices. ADA Professional Product Review. Council on Scientific Affairs. October 2016, volume II (2):1-6. https://www.dentalinnovationsllc.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ADA-PPR-Oct-2016.pdf.

16. Spomer J, Estrich CG, Halpin D, Lipman RD, Araujo MWB. Clinical perceptions of 4 hearing protection devices. JDR Clinical & Translational Research. 2017;2(4):363-369.

17. Guignon A. Can you hear me now? Hear about occupational noise-induced hearing loss among dental professionals. RDH magazine website. https://www.rdhmag.com/career-profession/students/article/16409266/can-you-hear-me-now-hear-about-occupational-noiseinduced-hearing-loss-among-dental-professionals. Published June 18, 2016.

About the Author

Sam S. Shamardi, DMD

Sam S. Shamardi, DMD, is a board-certified periodontist and clinical instructor at the Harvard Dental Division of Periodontics. While practicing full-time, he devotes himself to entrepreneurial ventures through his company, Dental Innovations LLC, with the goal of educating and protecting the dental industry from overlooked issues, including noise-induced hearing loss. He lectures nationally and internationally, and in his spare time enjoys traveling and following his favorite soccer team, Real Madrid.