Effective implant case presentation for the fully edentulous patient - presenting all the options.

Since the introduction of root-form dental implants to the United States in the early 1980s, its clinical success and popularity has grown steadily.1 Technical advancements in thread design, implant coatings, and implant connection have further improved the success rates seen with implants. Public perception of implants, though sometimes inaccurate, has come to recognize implants as a viable option for the replacement of teeth.2

Clinical lectures and hands-on workshops teach step-by-step procedures for surgical grafting, placement, and restoration of implants. To a lesser extent, some courses offer suggestions for treatment planning and case presentation. Presentation skills are a vital factor in gaining patient acceptance of implant cases. However, from conversations with numerous dentists over the past decade, we have found continued concerns about how to effectively offer implant options to their patients. Uncertainty about how to present the benefits of implants over other treatment alternatives seems more acute among restorative dentists, with certain exceptions.

Asked to enumerate the obstacles to implant case acceptance, dentists and staff personnel commonly list the following:

• Cost of treatment

• Extended length of treatment time vs. alternatives

• Lack of insurance coverage

• Fear of surgery; bone graft objections

• Poor public perception of implant success rates

It is apparent that clinicians must be able to articulate the benefits and value of implants in order to address these objections to treatment. Many patients perceive implants as prohibitively expensive. One of the principles of case presentation is to focus the patient’s attention on the benefits of implants before discussing the cost. This can be a significant challenge, because most patients ask for a cost estimate or, at least, a “ballpark” estimate as one of their first questions. Patients must be assured that all of their questions will be answered following a full review of their existing conditions and treatment options.

The length of treatment time has been streamlined significantly during the past few years. With “immediate load” cases, a provisional crown and abutment can be inserted at the time of implant placement or shortly thereafter. In other cases, the restorative process typically begins much quicker than we saw in the early to mid 1990s. For example, it is not unusual to begin final restoration in delayed loading, or “sequenced,” cases at two to four months versus the four to six month (or longer) period formerly employed just a few years ago.

Patient disappointment with a lack of insurance coverage also is a common complaint. Nevertheless, many dentists have learned to deal with this issue by pointing out the typical inadequacies and misrepresentations made to insured clients by various sources. Because coverage is often limited to $1,000 to $1,500 of annual benefits, the insurance component of payment represents a limited resource to the patient. The dentist’s task is to relate the benefits of implant treatment based on “out-of-pocket expenses” rather than insurance payments. Although these expenses may exceed the insured’s annual reimbursement allowance, alternative benefits may in some cases be paid and reduce the patient’s financial burden.

Concerns or objections regarding surgical procedures can be effectively addressed by the surgical dentist. For example, most patients can understand the necessity of bone grafting or ridge augmentation with visual aids, X-rays, models, photos, and other pertinent diagnostic information. While we have found that the surgical clinician is best-equipped by expertise and experience to discuss these issues, it is important for the restorative dentist to corroborate these needs so the surgical/restorative team speaks with a common voice. The impressive refinements and advancements associated with implant dentistry are largely due to the ability to graft adequate bone of sufficient quality for the rigid stabilization of implant fixtures. Obviously, general dentists who perform both surgical and prosthetic procedures need to be proficient in both areas of case presentation.

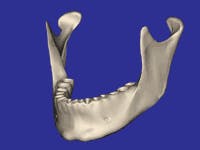

It is mandatory that you honestly address patient concerns regarding pain, swelling, bruising, paresthesia, and implant failure. Without minimizing these negative possibilities, attempt to balance their relatively infrequent occurrence against the positive final results contributed by the surgical procedures. Failure to proceed with recommended implant treatment often can result in a significantly reduced prognosis due to bone atrophy and poorer receptor sites for implants (Figs. 1 and 2). This should be a pre-eminent concept when discussing the advantages of implants to a prospective patient. Preservation of bone by insertion of root-form fixtures is a hallmark of implant therapy.

With the foregoing information in mind, the purpose of this article is to focus on case presentation for the maxillary and/or mandibular fully edentulous patient. Treatment planning for this patient requires diagnostic data including models mounted on a semi-adjustable articulator, panoramic radiograph, photos of the patient’s existing condition, and a comprehensive examination. In a “team” format, a surgical dentist is responsible for the placement of implants and grafting procedures, while the restorative dentist fabricates the definitive prosthesis. Both clinicians should be jointly involved in treatment-planning the case in advance of the surgical phase in order to achieve ideal results. Case presentation can be done jointly or separately with this approach. In some cases, the same clinician will perform both the surgical and restorative procedures. Regardless of the format, effective case presentation is essential to helping the patient make an informed decision about proceeding with recommended treatment.

In the fully edentulous case, possible options for treatment include:

• Full fixed bridgework cement- or screw-retained to implants

• Implant-retained removable bar overdenture

• Implant-retained removable attachment overdenture

• Fixed-detachable, or hybrid, appliance

• Conventional removable full denture

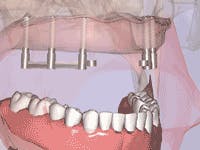

Each of these options must be verbally explained and, for best results, illustrated to the patient. For example, the full fixed bridge option is typically supported by a minimum of six implants; preferably eight or more implants. Advise the patient that the bridge can be either cement- or screw-retained, or a combination thereof (Figs. 3 and 4). Surgical risks and possible complications include postoperative swelling, bruising, hemorrhage, discomfort and, in rare cases, paresthesia. Postrestorative risks and complications can include fracture of the fixed-bridge porcelain and/or framework, screw-loosening, decementation, gingival inflammation and, in rare cases, implant failure.

Although implant failure must be noted as a possibility, replacement of the implant with success also is a common option. Clinicians should explain that they are medically and ethically obligated to note all the previously mentioned risks and complications, but that these are exceptions to treatment. The case presentation should focus on the fact that the great majority of cases are completed with a high level of patient satisfaction.

Although no one can guarantee success, we can put the record of implant success in perspective with other traditional therapy. For example, the 10-year survival rate of implant-supported restorations is about 95 percent versus about 75 percent for natural tooth-supported restorations. We should acknowledge that many such natural tooth restorations can have a longevity far beyond 10 years. Nevertheless, it is important to note that implant restorations have the highest statistical longevity of anything we do in dentistry today.

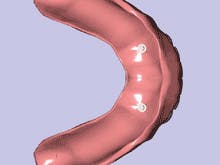

The removable options for the fully edentulous case include a bar-retained or attachment-retained overdenture (Figs. 5, 6, 7, and 8). The removable prosthesis allows the patient to clean the retaining bar or attachments with relative ease compared to fixed implant bridgework. In addition, the acrylic denture base can restore moderate to severe hard- and soft-tissue deficit with less complex laboratory construction. Traditionally, dentists have espoused fixed alternatives as being superior to removable ones in conventional dentistry, i.e. fixed bridgework vs. conventional full or partial dentures. Clinicians should present the positive characteristics of the overdenture to counteract any misconceptions about implants.

A significant benefit of the maxillary implant overdenture over the conventional full denture is our ability to expose a large portion of the palatal vault. I have observed and recorded numerous patient comments that verify increased patient satisfaction as a result of this feature. When the patients can feel the rugae of the palate with the tongue, they experience a renewed taste and texture sensation with foods that are denied with the conventional full denture. The psychological effect this has on patients enhances the positive attitude they develop from the implant overdenture. Accordingly, the patient begins to feel dentate again as opposed to the “second-class” status of full edentulism.

It is more powerful in a case presentation for the prospective implant patient to hear, read, and see actual patient testimonials than for the dentist to recite a list of attractive features. Patient comments in letter form can be inserted into the presentation where applicable. These testimonials are best retained in the patient’s own words in order for them to be credible. Videotaping completed implant patients’ comments are an even better way to convey the advantages of implant treatment. Some expertise and expense to the clinician is involved to produce a video that has adequate, clear audio and visualization of the patient. Real-world testimonials from actual patients who have experienced the proposed procedures and invested the finances for implant therapy are highly valued by the patient considering this treatment.

While enumerating the previously listed advantages of overdenture treatment, the clinician should also inform patients about the possible complications which may include fracture of denture teeth and/or denture base, bar fracture, and rebase or reline needs at certain intervals. The clinician should explain that such conditions are repairable and usually of short duration. Replacement of attachments is recognized as a routine and expected aspect of overdenture use. All other previously mentioned surgical and prosthetic complications are noted to be applicable to this option.

The hybrid, or fixed-detachable, appliance represents an option somewhere between those of fixed and removable restorations (Fig. 9). Technically, the hybrid is fixed in that the entire prosthesis is bolted into the implants. However, it also is “removable” in that the clinician can unscrew and remove it for maintenance or repair if necessary. Although applicable to restoration of both arches, it is more commonly fabricated for the edentulous mandible. This prosthesis traditionally requires four to six, or more, implants to support it.3 In the maxilla, four implants may be considered inadequate. This option was popularized with the original mandibular Branemark “high water” design which usually employed five or six implants.

The fixed aspect of the hybrid is attractive to some patients who do not like the idea of anything removable. Also, the more limited posterior extension, compared to the overdenture coverage posterior to second molar positions, may be favorable by its bulk reduction. The clinician must inform the potential hybrid patient about all previously mentioned implant complications.

The conventional removable full denture - the non-implant option - must also be presented in order to be comprehensive and medico-legally correct. The limitations of this option versus an implant prosthesis include less retention, generally more bulk in the denture base (full palatal coverage for the maxillary denture), continued atrophy or resorption of the alveolus, and less chewing efficiency. The primary advantage of the conventional full denture is that it costs less than the implant options. The clinician should provide patients with a realistic appraisal of these inherent limitations in relation to the financial investment involved for each option.

The case presentation can include radiographs, mounted models, and slides or photos of the patient’s existing condition. Demonstration models of representative implant cases from Models Plus (www.dentalmodelsplus.com; Kingsford Heights, Ind.) (Fig. 10), or video animation examples that illustrate the treatment options to the patient, or both, will significantly increase the presentation effectiveness. Digital photos of the patient’s current condition and digital examples of completed implant cases shown on a computer monitor can reinforce the patient’s perception of a technologically current office and clinician. However, we have found that patients may react negatively to clinical intraoral photos used as examples of treatment options. Accordingly, the use of animated examples serves as a less threatening means of communication. DVD or video programs that combine narration with animation maintain the patient’s attention to the subject matter without being offensive. Examples of this technology include the CAESY System (Caesy Interactive Systems, Toronto, Canada), “Click N Print” (Hands On Training, London, Ontario, Canada), and “Dental Implant Options and Alternative Treatment” (Millennium Productions, Tulsa, Okla.). The latter allows the patient to view all treatment options for any given existing condition with their risks and benefits, through narration and animation, all in about 12 to 15 minutes. The dentist or staff person can then procure the patient’s signature to affirm that he or she has viewed the video and understands its contents in order to fulfill the clinician’s informed consent responsibility. Additional patient questions or concerns also can be addressed by the dentist in a more efficient, timely manner because the patient’s understanding of implant procedures will be enhanced by viewing the video first.

Additional written, informed consent can be procured with forms developed by the International Congress of Oral Implantologists, or ICOI (www.icoi.org; Upper Montclair, N.J.). These forms should be reviewed by the dentist or staff in order to document the patient’s acknowledgement of having received a comprehensive explanation of proposed procedures. The ICOI, as a member benefit, offers both a Consent for Treatment form and a Request for Treatment form to satisfy this need.

In summary, the case presentation is an opportunity for the clinician to effectively convey -

✔ the value of implant treatment

✔ the risks associated with all options

✔ the consequences of failure to pursue recommended treatment

✔ documentation of informed consent responsibilities of the dental office.

Educated patients are more likely to understand and follow through with therapy that will enhance or restore their dental health with better function and esthetics. Should the patient elect not to pursue an implant, the dentist has advised the patient of the limitations or compromised results that the nonimplant option represents. A conscientious effort on the part of the restorative dentist preoperatively will reduce the chances of a disappointed or disgruntled patient stemming from unrealistic expectations. In addition, an organized, methodical, and professional case presentation enhances the patient’s perception of the clinician’s abilities. As a result, the patient often feels more disposed to move ahead with the investment of time and finances to complete the recommended procedures.

Author’s notes: The animation examples in this article are reprinted from the DVD version of “Dental Implant and Alternative Options: Featuring Informed Consent” with permission from Millennium Productions, 2004, Tulsa, Okla.

Editor’s notes: Opening graphic of smiling patient is provided by IMTEC Corporation, Ardmore, Okla. References are available by request. E-mail [email protected].

Dr. Samuel Strong is in private practice in Little Rock, Ark., and lectures nationally on implant dentistry. He is a member of the AACD, AAFP, ADA, and various other professional organizations, as well as a graduate of the Las Vegas Institute and the Baylor University Cosmetic continuum. He maintains Fellowship and Diplomate status under the ICOI, and is a Board Credentialed member under the Academy of Sleep Medicine. Reach Dr. Strong at (501) 224-2333, or visit www.strongdds.com.