How phasing restorative treatment can be helpful for both dentists and patients

Zachary Sisler, DDS

“What type of payment plans do you offer?” This is a common question heard in many dental offices, especially when a patient needs a sizable amount of treatment. Why? Because cost is one of the biggest factors preventing patients from getting the care they need.

But what if there were other options for patients—ones that didn’t make cost a barrier? What if there were an approach in which both dentists and patients worked together to formulate a solution to their needs?

An excellent, underutilized way to overcome the cost barrier—and others—is the process of phasing restorative treatment. When restorations are completed in multiple phases, patients can pay for treatment in smaller increments. This can reduce or eliminate the need for independent financing, which itself can add costs, such as origination fees and interest.

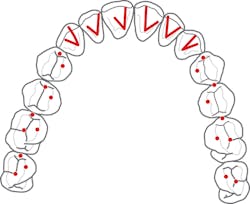

Figure 1: Requirements of occlusal stability

For example, let’s say a patient needs $20,000 worth of treatment, but at the time can only afford a small portion of this. The dentist then finds a way to phase the treatment while maintaining the biological and functional stability of the patient. When the phased option is presented, the patient is able to accept it. The patient understands immediate and future treatments—and their associated costs.

By phasing treatment, we can improve the functionality and esthetics for patients at a reasonable speed, while still respecting any emotional, monetary, or time constraints.

Understanding reasons to phase treatment

In addition to cost, phasing treatment can help patovercome common concerns. These concerns can be acknowledged and brought to the forefront of the treatment planning discussion to ease patients’ minds and gain their trust. Let’s look at these reasons more closely.

Physical—Some patients are physically unable to sit in a dental chair for an extended period of time. For example, TMJ and back issues can make extensive work in a single visit uncomfortable. This can cause patients to be hesitant to go through with treatment. In these cases, the goal should be to have shorter appointment times. Explain to patients that it is acceptable to take multiple breaks during appointments to reduce stress and discomfort.

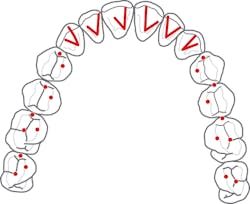

Figures 2–4: Patient presentation

Emotional—Many patients are self-conscious about their teeth. Easing into these conversations and approaching the topic delicately can reduce anxiety. By phasing treatment, patients can build confidence and feel more comfortable. They will be more likely to commit to more work as treatment progresses.

Mental—Some patients cannot or do not understand the need for their dental treatment. Helping educate them about the consequences of issues going untreated can open doors of opportunity. It often helps to have a spouse, family member, or friend join these patients when discussing their treatment plans. Dentists can discuss the risks of not going through with treatment, as well as the rewards of taking action through presenting similar successful cases. Having someone act as a sounding board can help provide clarity and create positive outcomes.

Financial—Money is likely the most common barrier to receiving treatment. Patients can feel that the treatment is simply too much to afford. The best question a dentist can ask is, “What does your budget allow for right now?” Many times, a dentist can find room to work within a budget, and this will allow patients to feel financially comfortable while receiving needed treatments.

Communicating treatment plans

Having open lines of communication between dentists and patients is key to gaining treatment acceptance. Expressing concern and letting patients know the consequences of inaction can open patients’ minds to the reality of the situation.

For example, a dentist can say, “Mrs. Jones, I’m starting to see some wear on your teeth. If you want to keep them for a lifetime, we need to talk about a plan for treatment in the near future.” This simple statement has two key points. First, the dentist recognizes the fact that the teeth are beginning to break down and the potential consequences. Second, it puts the responsibility back on the patient to take action.

Figures 5–7: Patient presentation

Communicating from a standpoint of true concern establishes a foundation on which to build treatment plans when patients are ready to accept them. It must be understood, though, that due to the cost of some comprehensive treatment plans, patients may need help in becoming ready and willing to pursue solutions for their issues. This is why having the conversation up-front about patients’ monetary constraints is a necessity. These conversations can save time and frustration for patients and dentists alike.

Biological and functional considerations

The goal of any treatment plan is to promote long-term stability for the patient. The success of a treatment plan hinges on the dentist’s ability to examine and diagnose two key components of patients’ overall oral health: biological and functional. Recognizing these components and maintaining stability in each phase is the only way to ensure a lasting, predictable result.

Biologically, a patient may have systemic issues, such as medications that cause dry mouth, airway issues, diabetes, hypertension, or other illnesses that need to be treated by a physician. Dentally, the patient may have abscessed teeth, caries, periodontal disease, or other conditions that require treatment. This component is often what is taught in dental schools across the nation.

Functionally, a patient may have TMJ issues with joint or muscle pain, wear, mobility, migration, or broken teeth. The dentist must determine the potential risk factors and causes of the functional issues to determine the best plan of action. The functional component generally goes beyond basic dental education and training.

It is important to understand that the dentist should not have a singular focus on either biology or function. The two concepts are intertwined and must be treated together with proper plans for phasing restorative treatment.

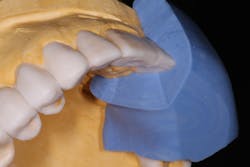

Figure 8: Silicone prep matrix of diagnostic wax-up

To manage the functional component, which will be demonstrated in the case report that follows, it is absolutely crucial to establish and maintain a sound occlusal scheme. There are five requirements of occlusal stability that need to be met and treated in order to stabilize a patient for the long term:

• Stable and equal intensity contacts on all teeth coinciding with centric relation

• Anterior guidance in harmony with the envelope of function

• All posterior teeth disclude during mandibular protrusive movement

• All posterior teeth disclude on the nonworking side during mandibular lateral movement

• All posterior teeth disclude on the working side during mandibular lateral movement

To summarize the five requirements of occlusal stability, see Figure 1.

If any one of the five requirements of occlusal stability is not fulfilled, the occlusion is considered to be unstable unless the patient has a substitute for the missing requirement, such as a tongue thrust in place of anterior guidance, or the patient has eliminated the need for the missing requirement, such as a Class III skeletal growth resulting in a more vertical chewing pattern.

When talking about phasing restorative treatment, or even with a smaller treatment plan, dentists cannot ignore the signs of instability and expect to achieve a long-term, stable result. A key component from a functional standpoint is fulfilling the five requirements in each phase. The patient can then return when ready to accept more treatment and still be stable throughout the phases of treatment.

Figure 9: Using prep matrix to ensure proper reduction

Case study

When patients are able to phase treatment and are happy with the results, they are happy to talk about their experiences. This patient, who we will call Janet, was a current patient of record and had seen a friend’s recently completed smile transformation. When Janet came in for her routine periodontal maintenance appointment, she inquired about potential options to esthetically change her smile (figures 2–4).

Janet alternated her recall appointments between our practice and a local periodontist. Therefore, when analyzing her biological component, the periodontist was consulted. It was determined that Janet’s periodontal disease was at a stable and maintainable state. She was clinically ready to move forward with further treatment.

Janet’s chief complaint was that her teeth were starting to wear and become shorter. She also had multiple shades from preexisting crowns and bridges. Overall, she felt that her teeth were flat and lacked definition (figures 5–7). Additionally, there appeared to be signs of functional instability that needed to be addressed. All of this was explained to Janet and a comprehensive, full-mouth treatment plan was discussed.

Janet was hesitant, as many patients are, due to the scope of treatment and cost. After discussing her goals for her smile and the financial considerations, she decided she wanted to focus on her maxillary teeth first. With this new set of parameters, it was determined that treatment could be broken down and phased over two to three stages in order to reduce the initial upfront cost. These were the treatment plan phases:

• Phase 1: Equilibration, crowns Nos. 3–14, composite bonding Nos. 22–27

• Phase 2: Veneers Nos. 21–28

• Phase 3: Crowns Nos. 20 and 29, implant crowns Nos. 19 and 30

Figures 10–12: Final restorations

The key thought process was that once the function and esthetics had been established for the upper arch, the lower arch could be completed one tooth at a time or several all at once. Having established and maintained the five requirements of occlusal stability, the lower-arch treatment becomes very routine and predictable dentistry.

For phase one, a diagnostic wax-up for the maxillary arch was completed. The wax-up serves as the blueprint for the newly desired esthetics and function. In trying to achieve anterior guidance in harmony with the envelope of function, the lingual contours of the maxillary anterior teeth are waxed up to ideal contours. This can then be transferred to the preparations using a silicone prep matrix and tested in the corresponding provisionals (figure 8).

During the first appointment, the lower incisal edges of teeth Nos. 22–27 were bonded with composite to restore the worn tooth structure. This was followed by preparation of the teeth for all porcelain crowns from teeth Nos. 3–14. The prep matrix was used to ensure proper reduction (figure 9). Once the provisionals were placed in the mouth, the five requirements of occlusal stability were established. The patient then tested these provisionals for one week and returned, stating no complaints with any of the esthetics, phonetics, or function. An impression of the approved provisionals was taken and then facebow-mounted in order to communicate all of the information to the laboratory for the final restorations.

Janet returned to the office for delivery of the final restorations and was thrilled with the results. She was officially finished with phase one of the treatment plan (figures 10–12). Her esthetic concerns diminished now with a smile that had every detail she desired, such as embrasure form, definitive line angles, depth of character, and incisal translucency (figures 13a and 13b). Since her initial concerns of esthetics and function had been stabilized, she would be able to come back and complete phases two and three on a timeline that worked for her. It was stressed that she would need to continue maintenance of the periodontal component.

Figures 13a and 13b: Before and after restoration

Conclusion

For patients who are ready to hear or actively seeking solutions for dental problems, phasing restorative and cosmetic treatment can be a path forward. The successful completion of phasing treatment is the result of the dentist meticulously examining each patient and determining risk factors for future problems.

By paying attention to details and establishing a stable, predictable, long-term prognosis, dentists can begin to break down potential barriers for patients accepting the treatment they need.

Zachary Sisler, DDS, is an associate faculty member for the Dawson Academy. In this position, he attends seminars and hands-on courses to mentor current students on their path to becoming comprehensive dentists. Dr. Sisler maintains a private practice in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, focusing on cosmetic, implant, and restorative dentistry.