Is cone beam really necessary?

In this monthly feature, Dr. Gordon Christensen addresses the most frequently asked questions from Dental Economics readers. If you would like to submit a question to Dr. Christensen, please send an email to [email protected].

Q

Almost every journal I read promotes the necessity of having a cone-beam radiographic device. I have been practicing adequately for many years, and I don’t see the need to spend a major amount of money on something for which I see no void in my practice. Am I wrong? What am I missing? Are my patients receiving substandard care simply because I don’t have a cone-beam device?

A

Your question is a very valid one. Only a small number of practitioners currently have a cone-beam device in their offices. The cost of this technology is high, and many dentists feel just like you—they don’t see why they should purchase a cone beam at this time.

Fortunately, you have asked a question I feel qualified to answer. I have used cone-beam radiographic devices in my office for more than 17 years. In addition, Clinicians Report Foundation, with my help, has evaluated many cone-beam devices during those years.

On a related subject, we recently conducted a survey of our readership to determine the percentage of dentists who have panoramic devices in their offices. We were surprised to find that about 25% of practitioners do not use panoramic radiography, which has been available in the profession for more than 60 years. These dentists must not sense a need for panoramic images, although these types of images are highly educational for both dentists and their patients. Undoubtedly, this group of dentists does not perform procedures that are best accomplished with the help of panoramic images, which relates to whether or not you need cone beam.

The first question you must consider is what procedures do you accomplish in your practice? If your practice is comprised primarily of treating caries with single-tooth restorations, you have a legitimate frustration about the potential need for cone beam. Conversely, if you are doing other procedures, cone beam is rapidly being recognized as essential. What are the procedures that are being enhanced markedly by cone-beam radiography?

Endodontics

Most general dentists do a few endodontic treatments every week. The researched information on endodontic procedures accomplished by general dentists shows that as high as 20% of these treatments are symptomatic after a few years of service. How can a practitioner determine why an endodontically treated tooth is symptomatic when using a two-dimensional radiograph? It is impossible to see some of the potential problems in such cases because the roots of a multirooted tooth are superimposed over one another. Further, resorptive lesions are often superimposed over the pulp, disguising the lesion. It is often difficult or impossible to see accessory lateral canals.

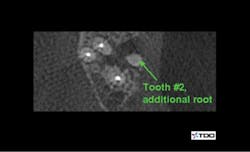

To date, endodontics is among the most necessary areas for cone beam. Another survey conducted by Clinicians Report Foundation found that most endodontists are now using cone beam. What potential problems do you see in endodontics when using a three-dimensional image? Often, a canal has been missed, such as the mesiobuccal canal in maxillary first molars. Frequently, there is another root present that is superimposed over the other roots and would be completely unidentifiable on a 2-D image (figures 1 and 2). Resorption can easily be hidden by the pulp, which is about the same level of radiolucency. Cracks in teeth can often be found by cone beam that cannot be seen with conventional 2-D radiographs.

Figures 1 and 2: Cone beam shows symptomatic maxillary second molar to have an untreated root. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Dale Miles.)

Removal of impacted teeth

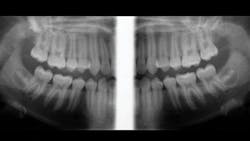

Although the exact percentage of general dentists removing impacted teeth is unknown, various surveys have reported this number as high as 50%. When removing an impacted third molar, it is highly desirable to know the exact location of the roots, their angulation, their proximity to the maxillary sinus or the inferior alveolar canal, and other characteristics. A panoramic image really helps, but a cone-beam image is even more helpful (figure 3). Having access to a cone-beam image of impacted teeth gives the clinician a higher level of understanding of the surgical situation and the apparent difficulties that may be encountered.

Figure 3: Extraoral bitewings made on a cone-beam device showing peculiar lack of development of third molars. Before removal, a cone-beam image is needed to show the exact location of the third molars.

Implant placement

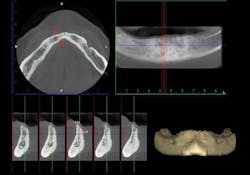

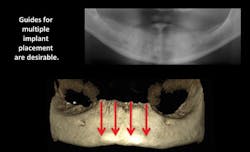

The percentage of general dentists who place implants is increasing significantly. Although implant placement has been common in dentistry for more than 30 years—performed primarily by freehand placement—guided placement is growing rapidly. Cone-beam radiography is necessary for fabricating implant-placement guides (figure 4). Research on guided placement shows that placing an implant with a guide constructed from a cone-beam image is somewhat more predictable and acceptable than freehand placement. This is especially true for the placement of multiple implants (figure 5).

Figure 4: Cone-beam images show minimal facial-lingual bone in the mandibular anterior area, requiring either small-diameter implants, bone grafting, or vertical removal of thin facial-lingual bone before placing implants.

Figure 5: Cone beam shows lack of bone in the posterior mandible and provides essential information about planning and placing four parallel implants in the mandibular anterior area.

Do I have to get a cone beam?

Most specialists who perform the three described procedures are using cone-beam images for their diagnosis and treatment. In my opinion, these three procedures will drive those general dentists who also perform the same procedures to at least have access to cone beam. Does that mean that all general practitioners who do these procedures should have a cone beam in their offices? No, it means that (1) they should be knowledgeable about the significant additional information that is available when using cone beam, and (2) they should find a place in their communities where they can get access to cone-beam images for those necessary procedures.

The following methods can allow practitioners to have cone-beam images either with or without buying a device:

- Buy a device for your individual office. This is the most adequate method. Cone-beam prices have come down markedly since their introduction many years ago, and purchase is not as formidable as it was when the concept was introduced.

- You and other dentists in your immediate area could go in together to buy a cone-beam device and place it in a convenient location for use by all parties.

- Find another practitioner in your area who has a cone beam and contract with that person to have images made for your patients.

- Locate a radiographic clinic in your area and arrange with that group to make cone-beam images for your patients.

Whichever of these suggestions you elect to integrate into your practice, I suggest that you take a cone-beam course so that you will be able to interpret the images yourself. If that does not appeal to you, there are many oral and maxillofacial radiologists who are eager to help.

I have suggested three types of procedures that will eventually motivate you to become involved with the use of cone beam, but there are many more.

Effect of cone-beam images on diagnosis and treatment planning

Over the several decades that I have been practicing dentistry, I have seen clinical situations that I never would have been able to observe without the benefit of cone-beam technology. I have treated some of these cases with the help of my competent team, while others have required referral to other practitioners, mainly ENT physicians.

The addition of cone beam to any dentist’s practice significantly increases that practitioner’s diagnosis and treatment-planning ability, excites patients, and provides a new and enhanced level of patient care.

Summary

Ready or not, cone-beam imaging is here. The benefits are many, the cost is high, the education provided by the concept is outstanding, and the improvement in patient care is obvious. However, dentists should evaluate the procedures they offer to determine how this technology can or cannot be used in their specific practices.

Author’s note: Additional educational resources are available from Practical Clinical Courses, some of which relate directly to this article:

Two-day courses in Utah

• Implementing Cone Beam Imaging into Your Dental Practice with Dale Miles and Dr. Gordon Christensen: June 1–2, 2018

• Implant Surgery—Level 1 with Dr. Gordon Christensen: September 7–8, 2018

One-hour CE videos

• Implementing Cone Beam CT Imaging into Your Practice (Item No. V1174)

• Top Insurance Coding Strategies (Item No. V4783)

For more information about these educational products, call (800) 223-6569 or visit pccdental.com.

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD,is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah. He is the founder and CEO of Practical Clinical Courses, an international continuing education organization founded in 1981 for dental professionals. Dr. Christensen is cofounder (with his wife, Dr. Rella Christensen) and CEO of Clinicians Report.

About the Author

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD, is founder and CEO of Practical Clinical Courses and cofounder of Clinicians Report. His wife, Rella Christensen, PhD, is the cofounder. PCC is an international dental continuing education organization founded in 1981. Dr. Christensen is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah.