Dental cementation: Evolution to revolution in everyday dentistry

The myriad of choices and protocols in the rapidly expanding market of dental luting cements has led to an abundance of decisions for dental professionals, and perhaps even created a bit of confusion when deciding which dental luting agent to use with the various indirect restorations.

Dental luting is an adhesive substance that creates an intimate seal between the dental restoration and the prepared tooth structure, thereby preventing dislodgment of the restoration.1 The success and longevity of a restoration starts from the critical components of an initial comprehensive exam, moving to diagnosis, treatment planning, preparation, design, restorative material selection, and finally, selection and seating of the dental luting agent. The increase in indirect restorative materials—ranging from all-metal, porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM), all-ceramic, and zirconia—has warranted a cementation process that’s more selective and variable, providing more options for the clinician.2

This selection process is a vital component in the overall clinical success of the restoration. Different restorative materials may warrant different luting agents, depending on the tooth location, preparation design, prep shade, and location of the margin.3 As the science of luting agents continuously advances, many kinds of luting cements have become available. Some factors to consider when selecting a proper luting cement include biocompatibility, adhesion, mechanical properties, solubility, handling, and radiopacity.2

The evolution of dental luting cement

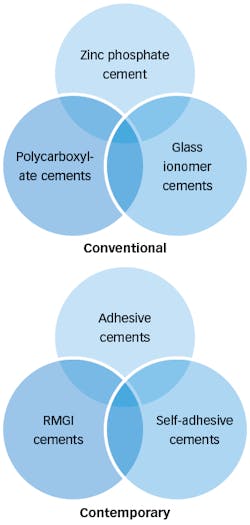

Before modern dental luting cements, conventional cements included zinc phosphate, polycarboxylate, and glass ionomers. These cements paved the way for the development and science of the contemporary cements we use today.3

As the first dental luting cement, zinc phosphate was regarded as the gold standard for many decades, as it offered low sensitivity, low cost, high compressive strength, and low tensile strength. The disadvantages included a powder and liquid mix, using a cool glass slab, long mixing time, and a set time that could take up to nine minutes after mixing.

You may also be interested in ...

Cementing zirconia restorations

How to reduce recurrent caries and crowns coming off

Polycarboxylates offered the same disadvantages along with low tensile strength, low compressive strength, and a less-than-ideal film thickness.4

As the science of dental luting agents evolved, glass ionomers made their mark in the cementation era of the 1960s, with desirable handling properties, quicker set time, better compressive and tensile strength, and fluoride release with anticariogenic effects.

Eventually this led to the development of one of the most popular contemporary cements today: resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) cements.1 These pioneer luting cements gave rise to the evolution of cements most widely used today. Contemporary cements include RMGI cements, self-adhesive resin cements (SARC), and conventional resin cements (CRC).

The nomenclature and description of dental luting cements described in the literature can exhaust and confuse clinicians, as there are many different descriptions for the same luting cements. The terms conventional and contemporary have been used to describe and delineate where we were and where we are now in the science of dental luting cements (figure 1).

RMGI cements (e.g., GC FujiCEM 2, GC FujiCEM Evolve, and 3M ESPE RelyX) have gained popularity due to the ease of handling properties, low sensitivity, extended fluoride release, and lower water solubility than their predecessor, glass ionomers. RMGI cements have a dentinal bond strength to tooth structure less than that of resin-based cements.5 When selecting an RMGI, attention to the retention and resistance form of the preparation must be considered as RMGIs may be a disadvantage in nonretentive preparations. RMGIs are recommended in highly retentive preparations with restorations such as zirconia, PFM, and all-metal restorations.

The resin cements described as CRC (e.g., G-CEM LinkForce, 3M RelyX Veneer Cement, and Ivoclar Variolink Esthetic) offer the benefits of high bond strength, low water solubility, high compressive and tensile strength, and ideal performance in both posterior and esthetic cases. The adhesive systems in CRC systems can be divided into total-etch, selective etching, and self-etch.4 The total-etch technique poses a higher risk of postoperative sensitivity to dentin, though it is more advantageous in enamel preparation when compared to the other etching techniques. Self-etching adhesives may offer some benefits, but the etching of enamel is less effective than with phosphoric acid.6 A combination of etching just enamel or selective etching with the use of self-etching adhesives can increase bond strength and minimize sensitivity.7

As this category of resin luting cements has gained popularity, clinicians may find isolation to be challenging and that they require a more technique-sensitive approach (i.e., etching, priming, and bonding of both the preparation and restoration). In these cases, multiple steps are needed to achieve a successfully bonded restoration.8

Self-adhesive resin cements

The success of the adhesive system is directly proportional to the clinician’s ability to successfully deliver the restoration to the patient with ease and confidence in a timely manner. The last decade of luting dental research has targeted SARCs for this reason.5 SARCs provide a strong bond and low postoperative sensitivity.

The mixture of monomers, filler, and activator initiator systems allow for a strong bond between the tooth substrate and the restoration without the need for a separate etching agent or adhesive. When not using phosphoric acid, the bond to enamel is not as strong5,8; therefore, SARC is an excellent luting agent as neither the tooth nor the restoration needs to be treated at the time of delivery. SARCs may represent an efficient choice, which can be as reliable as the multistep resin adhesive cements with low postoperative sensitivity.

As SARCs have created a large footprint in our dental market today, other names that describe this concept include self-adhesive universal resin cement and self-adhesive luting agent. One product, GC America’s G-CEM One, has gained tremendous popularity for its all-in-one use for luting zirconia and LiSi glass ceramics.

Clinical case using universal resin cement

The cementation process has many variables, and sometimes clinicians are confused as to which luting agent to use, when to use to it, and more importantly, why.

A universal resin cement, such as G-CEM One, creates an adhesive system that handles with ease, provides dependable bond strength to both the tooth structures and restorations, and allows bonding to multiple substrates. It can be used as an SARC, a CRC, and an all-in-one system. G-CEM One has a unique feature: it contains the effective and successful monomer, 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (MDP). With the presence of MDP, a strong chemical reaction is established between the MDP and the hydroxyapatite of the tooth structure. G-CEM One is an ideal cement for everyday dentistry as it is compatible with restorations for all-ceramic materials, including silica-based (e.g., lithium disilicate) and nonsilica-based (e.g., zirconia restorations), and has good retention. It can also be used as a CRC with the application of G-CEM One Adhesive Enhancing Primer (AEP) on the tooth structure and a universal primer (G-Multi Primer) for situations with low retention.

Cementation of zirconia with high-retention crown

Zirconia posterior restorations can provide a strong and durable outcome with minimal preparation. Bonding to a high-retentive prep with proper retention, resistance form, and taper, the cementation protocol includes preparation of the zirconia crown and G-CEM One cement.

Step 1: Properly clean and air abrade your zirconia restorations with small alumina oxide particles (30-50 microns) set at low pressure (30 psi or two bars). The restoration is now ready for cementation (figures 2 and 3).

Step 2: Fill your restoration with G-CEM One cement and seat. A one-second light tack cure makes the cleanup simple and efficient (figures 4-7).

Step 3: Completed restorations (figures 8 and 9).

Bonding to glass ceramics or lithium disilicate

Lithium disilicate offers impressive esthetic results and provides a high strength for restorations in anterior and selective posterior areas. G-CEM One can be utilized as a resin cement when prep retention is low in the posterior areas.

Step 1: After proper cleaning and etching (with hydrofluoric acid) of the restoration, apply G-Multi Primer to the restoration (figures 10-12).

Step 2: Apply G-CEM One AEP on the preparation (figures 13 and 14).

Step 3: Fill your restoration with G-CEM One cement and seat. A one-second light tack cure makes cleanup simple and efficient (figures 15-17).

Conclusion

Dental cementation has revolutionized modern dental cementation protocols, bringing ease of use and predictability to the clinican and longevity to the patient. Universal resin cements, such as G-CEM One, are known for their universal all-in-one applications and have become the Swiss Army knife of cementation with a unique formula for various clinical applications in dentistry. Universal resin cements have all the advantages of self-adhesive cements and can also be used as resin cements in certain situations.

Editor’s note: GC America is a recent financial supporter of Dental Economics. This article appeared in the May 2023 print edition of Dental Economics magazine. Dentists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Leung GKH, Wong AWY, Chu CH, Yu OY. Update on dental luting materials. Dent J (Basel). 2022;10(11):208. doi:10.3390/dj10110208

- Swift EJ Jr. Contemporary dental cements. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24(6):365-366. doi:10.1111/jerd.12003

- Lad PP, Kamath M, Tarale K, Kusugal PB. Practical clinical considerations of luting cements: a review. J Int Oral Health. 2014;6(1):116-120.

- Sakaguchi RL, Ferracane J, Powers JM. Materials for adhesion and luting. In: Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials. 14th ed. Elsevier; 2019:273-340.

- Mante FK, Ozer F, Walter R, et al. Current state of adhesive dentistry: a guide to clinical practice. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013;34(9):2-8.

- Manso AP, Carvalho RM. Dental cements for luting and bonding restorations: self-adhesive resin cements. Dent Clin N Am. 2017;61(4):821-834. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2017.06.006

- Weiser F, Behr M. Self-adhesive resin cements: a clinical review. J Prosthodont. 2015;24(2):100-108. doi:10.1111/jopr.12192

- Pongprueksa P, De Munck J, Karunratanakul K, et al. Dentin bonding testing using a mini-interfacial fracture toughness approach. J Dent Res. 2016;95(3):327-333. doi:10.1177/0022034515618960

About the Author

Michelle M. Lee, DMD

Michelle M. Lee, DMD, is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, where she teaches restorative microscope dentistry and then integrates it into her comprehensive restorative private practice in Fleetwood, Pennsylvania. She serves on the Pankey Board of Directors and faculty, as well as holds a Pankey Scholar distinction. Dr. Lee is a spokesperson for GC America, and products mentioned in her articles are used regularly in her practice.

Updated March 31, 2023