Lease vs. buy: Equipment, cars, and buildings

How to navigate through the mine fields of interest rates, payment terms, taxes, and deductions.

by Rick Willeford, MBA, CPA, CFP

Since dentistry is an equipment-intensive business, you continually are faced with lease vs. buy decisions. This article will dispel a few myths, give you some solid numbers to compare, and give you some insight into pitfalls to avoid. Although the leasing environment is totally different for equipment, cars, and buildings, our clients continually have questions in these areas, so it should be helpful to discuss all three areas.

Equipment

More than half of all equipment acquisitions are financed by leasing companies, so you need to be able to make an informed choice when this important decision arises.

A lease is not a lease is not a lease. Most folks equate "leasing" with "renting," but this may not be true. There are two kinds of leases: an "operating" (true) lease, or a "financing/capital" (purchase) lease. The operating lease is the "rental" approach. It is characterized by an option to buy the asset at the end of the term for fair market value, with a minimum payment of 10 percent. In such an operating-lease arrangement, you can fully deduct the monthly lease payments as you pay them. Since you do not own the property, you do not depreciate it.

The financing or capital lease is similar to using a bank loan to make an outright purchase. (This also may be called a Conditional Sales Contract.) Like a typical loan, there is no buy-out at the end, because you own the property from the beginning. This means you depreciate the property and deduct only the interest part of the payments. The leasing company does not care which approach you use, and it typically gives you several variations of both options.

- Tip: Sometimes it pays to use a true lease to pay for building improvements. This avoids the requirement to depreciate over 39 years!

- Trap: Sometimes there is a requirement vs. an option to pay 10 percent at the end of the lease. If it's a requirement, it's not a true lease!

Cost of lease vs. buy. Financing from a leasing company has many advantages — but let's be clear: cost saving is not one of them! The ability to deduct operating "true" lease payments as equipment rental vs. the requirement to deduct the equipment depreciation over seven years with a purchase does not offset the operating lease's higher interest rate. But, the cost difference is fairly insignificant. Conversely, one may be pleasantly surprised that enjoying the advantages of leasing may not cost a great deal more than a loan/purchase.

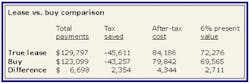

Example: Assume you want to finance $100,000 worth of equipment over five years. A 100 percent financing bank loan would require monthly payments of $2,052 at 8½ percent, while a true equipment lease would be $1,997 at 10 percent. Assume you will buy the equipment for $10,000 at the end of the lease, and that you are in the 31 percent federal and 6 percent state marginal-tax brackets. Should you choose the loan or the true lease? (See the comparative table below.)

- Tip: To be conservative, I have not assumed any first-year Section 179 depreciation deduction or ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) credit. Those items would reduce the net cost of buying even more.

- Trap: Beware of "interest" rates being quoted. You want a true effective rate, not some bogus "streaming" or other kind of rate. Have your CPA calculate true rates for you.

If cost is your main criteria, you should choose the purchase option. Here's why: Taking into account the total amount of payments, the timing of the payments, and the timing of the deductions, (assuming you will invest any early savings), the lease option costs $2,711 more than the purchase option.

Let me explain. First of all, a superficial look at the higher total payments of $6,698 in the chart above does not tell the whole story. The higher payments result in higher tax savings of $2,354, so the net after-tax difference is only $4,344. However, that's still not the whole story. It doesn't take into account the timing of when you make the payments and when you get to enjoy the tax deductions — the "time value of money."

For instance, if you are given the choice of receiving one dollar to invest now or the same one dollar to invest a year from now, you would prefer to have the dollar now so you can invest it sooner. In fact, if you can get a 6 percent investment return, you would say that receiving the dollar one year from now is the same as getting about $.94 today. (You can invest the $.94 at 6 percent and have the dollar in a year.) We say that $.94 is the present value of the dollar in one year, assuming a 6 percent return.

Therefore, taking into account the timing of payments and deductions, and assuming you will invest any early savings, the lease option still costs $2,711 more.

So why ever lease? Potentially, there can be some significant advantages. At a minimum, leasing offers the traditional trade-off of convenience vs. cost: leasing companies typically can offer more flexible terms than a bank. In addition, leasing often is the only way to get a transaction financed, regardless of the cost.

Typically, a bank is happy to make you a loan if you have plenty of collateral (the classic case of being willing to lend money to folks who don't need it!). The bank may limit a loan to 80 percent of the cost of the equipment (hence, my 100 percent financing assumption above may not be valid!) In the case of a practice purchase, it becomes even harder to get bank financing, since there is not much tangible equipment or other collateral as security. This is why a bank often asks for a cosigner to guarantee the loan, or it will want a mortgage on your home.

There is a big "however," though. If you have a strong personal relationship with an individual banker, that banker has some latitude and may lend you money based on your character and future cash flow. Clearly, maintaining such a relationship is more important than always chasing one point of interest savings by jumping from bank to bank. You also may find more flexibility when dealing with a local or small regional bank. Even the large banks go through cycles of seeking out health-care businesses, and some may have special departments to handle loans for physicians and dentists.

If you find a bank that will make the loan at all, it typically will not offer the same flexible-payment options as do leasing companies. While a bank may offer you a certain period of paying "interest only," a leasing company can customize graduated payments to meet your needs. For example: zero payments for three months, then partial payments for another three months, etc. Keep in mind, however, there is no free lunch. So have your CPA calculate the true interest cost associated with this flexibility. Be aware that banks typically will avoid making the loan for a term of more than five years. A leasing company will go seven or 10 years.

- Tip: A lease may not affect your bank credit, since a lease does not show up as a liability on your balance sheet or on your credit report.

- Trap: Determine the prepayment terms in case you want to pay off the loan early!

Automobiles

This truly is the trade-off of cost vs. convenience. If you equate "cost" with "monthly payment," then a lease certainly looks attractive. In fact, if you insist on driving a new car every few years and assume you will be making payments forever anyway, then a lease may not be all bad. But if you prefer the financially prudent approach of driving a car for a long time, you may already have discovered the problem with leasing: in exchange for your low payments, you do not own anything!

In fact, the leasing companies are in financial trouble now because they set the residual values of their cars unrealistically high to keep the monthly payments low. They are discovering that neither the driver currently leasing the car nor the general marketplace will pay those prices.

In leasing, there are several "gotchas" to contend with. You or someone you know may already have discovered that you can't just cancel a lease in the middle of it and walk away. You essentially have signed a long-term "financing" agreement. The payoff amount required to get out of a lease typically is more — often much more — than the car is worth. Hence, the expression of being "upside down" in your lease. Guess who pays the difference if you "total" the car in a wreck and the insurance company only pays for the car's depreciated value vs. what you owe? That's right, you!

Also, you may not be finished with it even after you've made all the payments. You may have to pay for "excess" miles you put on the car. Your limit may have been as low as 12,000 miles per year. Unless you can walk to work, that is not many miles these days.

So, what about the tax benefits? First of all, the business portion of a vehicle is deductible whether you own it or lease it (or whether it is owned/leased by either you or your corporation, for that matter). Business use is business use. Some of you may be astute enough to know that the IRS limits depreciation to the equivalent of a car worth $15,000, and you may be hoping that a lease can skirt these limitations. Sorry, the IRS limits the amount of the lease deduction in a similar manner. In truth, the lease limitation is not quite as onerous as the depreciation limit, so there is a minor advantage to leasing.

Leasing may make sense if you trade cars regularly and do not put over 15,000 miles annually on a car. The bad news is that, if that describes your habits, you may have bigger financial issues to deal with! Remember, the great investor Warren Buffet buys and drives used Fords ...

Office building

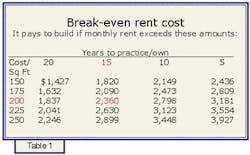

From the purely financial standpoint, the lease/buy decision depends on how long you plan to keep the building and how much it costs to build. In this analysis, the intangibles such as better office space, a different part of town, attracting new or different patients, etc., are not considered. The tables that follow will give you a rule of thumb as a starting point, and they do take taxes and the time value of money into account.

The tables assume you will sell the building when you quit practicing, with the following assumptions:

- Increase space from 1,800 square feet to 2,400 square feet, since most folks expand when building

- Increased property tax and utilities as an owner equals $2,000 per year.

- Increases of rent, taxes, utilities, and building value at 3 percent per year

- You invest the savings at 6 percent per year

- 20-year building loan at 11 percent to be conservative

- 40 percent income-tax bracket

- 25 percent federal/state capital gains tax on sale of building

- No increase in production — very conservative

The break-even rent cost (Table 1) shows the level of rent payment at which point you would be better off to own the building. For example, assume you expect to own the building for 15 years. If you can build for $200 per square foot (including land), then you would be better off building if you are paying $2,360 or more to rent 1,800 square feet.

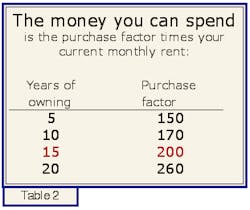

Stated another way, Table 2 shows how much you can spend on a building regardless of the number of square feet. (The figures still assume a 30 percent increase in size.) For example, if you are going to own the building for 15 years and you currently are paying $2,000 in monthly rent, you could spend about $400,000 ($2,000 x 200) on a building and break even in the long run, considering the ultimate gain on the sale of the building.

As you have learned in your profession, the answer to the "lease vs. buy" question often is "it depends!" While it is important to have your accountant help you determine the true cost of each option, you need to weigh the intangibles such as convenience, payment flexibility, and the total amount of financing available to make both informed and satisfying financing decisions.