Cosmetic ImagingA Communications Slam-Dunk

Author joins search on why cosmetic imaging is so popular. Here is the first part of the survey's results.

by Jean A. Sagara

We began this series on dentist-to-laboratory communications in January. Our goal was – and continues to be – the presentation of timely communication issues that impact this exchange of clinical information. For each article, we have taken an issue and informed it with views from various industry participants who are stakeholders in successful dentist-to-lab partnerships. Essentially, the articles pose problems and advance solutions and visions for how future communications will evolve. Authenticity, pluralism, and balance guide our choice of topic, range of expertise revealed, and selection of divergent viewpoints.

With that in mind, my colleagues and I set out to capture a small, but representative, cross-section of professionals to comment on the increasingly popular practice of cosmetic imaging. Why cosmetic imaging? We were drawn to this topic because it seemed to represent the quintessential example of successful communication between the dentist and the lab. As such, it was logical that an issue illustrating good communication would deserve a closer look. It also is a technique used by more and more dentists to provide information to patients. We learned that when such information is presented visually, the odds of case acceptance increases. As a communication tool and as a treatment strategy, cosmetic imaging appears to be delivering value at many levels: clinically, without a doubt, but also as a relationship builder for the dentist and patient, for the dentist and lab, and for the practice and the market.

The professionals with whom we spoke agree that cosmetic imaging is a popular service – easy to use and producing strong returns. Most of these also agree that it is a growing service. Still another point, however, persuaded us to take a closer look: Cosmetic imaging may be an analogue for the future of dentist-to-lab communications; it would seem to represent an example of how dentist-to-lab behaviors are changing. If that is true, then it may be a harbinger of the way dentists and labs begin to talk to one another and the way they create that dialogue.

Cosmetic imaging is not used solely for cosmetic restoration cases where its contribution is straightforward and obvious. It is becoming appreciated for the more subtle values it brings to case planning with the lab and case acceptance with the patient on long-term, complex treatment plans. We also suggest that it is an early manifestation of how easy and successful a digital conversation can be. While many dentists still provide their labs with actual photographs of the "before" patient, then receive "after" simulations from the lab, more and more people are using email and online templates to convey the images. It is the preferred communication venue. As patients and dentists link online with greater frequency (as well as dentists and labs), we predict that this digital traffic will expand. Web networks will make clinical processes more efficient and effective – and essentially just one click away.

Motivated by a curiosity to learn how cosmetic imaging is perceived in the industry, we attended the 2002 Yankee Dental Conference in February. We determined to enlist a small number of industry players including dental labs, cosmetic imaging providers, practice-management software companies, and dentists to participate in a dialogue with us. Using a survey, these participants recorded their views on cosmetic imaging, as well as their thoughts on the challenge and future directions of the dentist-to-lab communication dynamic.

For a listing of our survey participants and their products or services and information on other cosmetic imaging resources, please visit www.transcendonline.com and click on Jean's Resource Links.

In this issue, we present the first of a two-part series on cosmetic imaging based on our survey findings. We begin by presenting the viewpoint of the service delivery industry. This includes summary feedback from the dental labs and imaging providers of both the stand-alone imaging services and imaging software providers, as well as practice-management software companies that make cosmetic imaging applications. In the May issue, we will offer feedback from dentists to examine whether their perceptions and thoughts on communication challenges match up with the views of the service delivery respondents.

When the surveys are considered together, certain consistent observations emerge. For one, all participants agreed that cosmetic imaging improves the quality of information being sent to the lab, because anything that is visual does that. You may find such a validation rather obvious if taken at face value.

We remark, however, about the significance of this development to the total clinical process. Before cosmetic imaging came into vogue and regardless of whether photos were mailed to the lab or images were sent online, only the dentist knew what the patient looked like on any given case. It was and is still the rare lab that has a patient come to its facility even where it is legal to do so. The patient's face, with its contours and unique physiognomy, was inaccessible to the lab, the role of which was to execute a customized fabrication that would accommodate that person. This meant that the lab had to rely solely on the precision and accuracy of the specifications supplied by the dentist. The dentist, on the other hand, had to rely on the lab's accurate interpretation and execution, with both sets of expertise being determinative. Buttressed by a great deal of telephone conferencing, this usually worked. While that sort of consultation still persists (and should, according to our lab respondents), cosmetic imaging has introduced the patient to both parties.

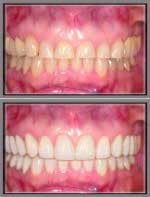

Bottom: The simulation concentrates on the prerestorative periodontal surgery requirements to increase cervical length. The simulation can be phased to show interproximal spaces and root morphology prior to the simulated restoration

As Larry Brooks, owner of SmileVision in Chestnut Hill, Mass., a cosmetic imaging provider for 13 years and an independent laboratory, said, " ... cosmetic imaging provides a tooth arrangement that is harmonious with the facial features." Here is communication as context. Indeed! The Mona Lisa's smile is what makes her portrait so enigmatic. Yet, could we imagine Leonardo DaVinci painting Mona Lisa's smile absent her face?

The survey also mixed it up a bit when it came to the value of cosmetic imaging as a communication venue with the patient. There was a difference of opinion. In particular, some respondents were cautious about the inherent danger of creating unrealistic expectations with patients who are eager to move from "before" to "after" in their cosmetic restoration program. Since the "after" image is simulated, they argued, what you see is not necessarily what you will get. In the end, this may be a reflection of the expertise of the lab, the dentist, or simply the way the dentist managed the chairside communication with the patient. Such feedback is reasonable based on the occasional experience. We will discuss this issue more fully when we consider the dentists' views.

While not all participants were equally enthusiastic about the benefits of cosmetic imaging, and a few labs admitted to using it sparingly, the majority of the survey participants underscored its positive contribution toward improved communications. One imaging provider, SmileArt Communications, calls it "... the ultimate communication tool." We take their point.

Judging from the types of participants in our survey and what services they offer, it was clear that a full range of delivery options is available in the market. For the dentist who may be interested in adding cosmetic imaging services to a practice, there are three choices:

1. Cosmetic imaging service provider – a fee-for-service arrangement with an imaging specialty provider such as SmileArt Communications, affiliated with DaVinci Dental Studios in Hollywood, Calif., where cosmetic creations are legendary. Other companies offering this service include SmilePix, a digital photo-imaging service in Essex, Conn., and SmileVision, mentioned above. With these services, there is no capital investment or learning curve with software. Similarly, there is no long-term commitment. If the results disappoint, the dentist can take an easy exit.

2. Practice-management software – an imaging simulation module increasingly available in practice-management software suites. Examples include EagleSoft, a Patterson Company; Dicom Digital Imaging Suite, now owned by PracticeWorks, Inc.; and Image 3.0 from Dentrix Dental Systems, Inc. These are of particular interest to the dentist who prefers the benefit of full integration with back-office administration.

3. Stand-alone cosmetic imaging software – dentists purchase this option and install it on the office computer. One example is CosmetiX, a dental-imaging simulation module from SciCan, Inc., a division of Lux & Zwingenberger, Inc. Another product is the Digital Dentist Imaging System offered by Digident, Inc. For these and many other similar products, the dentist and staff receive training on the use of the technology as well as support for maintenance and upgrades. These stand-alone products appeal to the dentist looking for total control over imaging services.

The survey substantiated our own informal observations, namely that no significant barriers existed for anyone desiring to provide cosmetic-imaging services. We deduced that the "buy" decisions were usually driven by the degree of up-front technical commitment required, the amount of capital investment necessary, or the desire for full-office integration with an existing practice-management system. No matter the approach, there was unanimity that cosmetic imaging could increase the opportunities to ...

• improve case acceptance

• improve information values

• create greater accuracy with the lab

• enrich the clinical process

• market more effectively

• expand capability

• increase profitability

Perhaps most significant, the survey revealed a growing recognition for the role that technology plays in clinical case management. In particular, it highlighted the contribution from digital and online communications. Technology linkages such as email, online lab-script templates, Web-enabled laboratory prescriptions with image uploads, and other "e-tools" were supported by survey participants. In fact, the survey respondents cited the emergence of the "high-tech dental practice" as a significant driver for increased demand for digital solutions. It was evident in reading the surveys that cosmetic imaging falls into this category.

To further illustrate this point, survey respondents indicated that they most often exchange "before" and "after" images in one of three ways: by email, online, or on a disk. Sending photographs through the mail was not a preferred method. Traditional film or photos sent through the mail will be used less and less as digital photography becomes the norm and online clinical transactions are only a mouse-click away. Digital, particularly Web-enabled, clinical communications have arrived.

The majority of respondents from the service industry believe that cosmetic imaging is a powerful and easy-to-use improvement to information exchanged between the dentist and the lab. Many predicted an annual increase in use of between 15 and 20 percent. Evidence for this growth is the value attached to cosmetic imaging as a case-management tool in a broad range of treatments. The survey reflected almost universal acknowledgement that cosmetic imaging can serve far more than just the typical tooth-whitening case. Participants identified the technique as very helpful for all types of cosmetic restoration work, notably for veneers, crown and bridge fabrications, closing diastemas, periodontal interventions, orthodontia, and even implant treatment plans.

Cosmetic imaging has become an important adjunct to the dentist and laboratory partnership. Seventy-seven percent of survey participants rated its value to the success of restorative work (on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest) between 7 and 10. When we asked them to evaluate the future of the technology using the same scale, 62 percent judged its future very high, again between 7 and 10. Thus, whether it is with the dentist and the lab, the dentist and the patient, or even the dentist and third parties (another possibility; not offered by any survey participant), cosmetic imaging delivers a visual punch that cannot be ignored. It expands information and refines the understanding for fabrication.

Cosmetic imaging is a fine example of market-driven success. It has gained in popularity as aesthetic dentistry and the willingness to leverage technology has grown in importance throughout the industry. It can help build a practice and support patient retention. From a technological standpoint, it offers easy access and ready appeal. Today, cosmetic imaging is recognized more and more for its broad clinical utility. Whether driven by consumer education, the demand for aesthetic enhancements, the general dentist morphing into a higher-end practitioner, or accessible technology, cosmetic imaging is a critical information resource. Cosmetic imaging teaches us that "simple" works. It also reaffirms an old adage: One picture is worth a thousand words.