Effective initial exams: The predictable route to practice success.

by George Salem, DMD

I can guess what most of you are thinking: "What a boring subject ... I don't want to read this ... I don't need to read this ... I already know how to do an oral examination ..." The truth is that most dentists do not deliver a thorough, systematic, educational, and, most importantly, motivational initial examination experience to their patients. Instead, they do a "quickie" (read: "wing it") examination at the patient's first visit while a cleaning/prophylaxis is carried out. Despite what any practice-management consultant may advise, this a mistake of the highest magnitude. Furthermore, dentists are regularly misled into believing that providing a wider array of services or block scheduling or installing new equipment, etc., will enhance their bottom line. "Add anti-snoring devices for an increase in production of $3,000 per month, night guards for $4,000 per month, laser dentistry for $5,000 per month, implants for $6,000 per month for a grand total of $216,000 of additional income to your practice by year's end." All of this is pure folly if you, the dentist, cannot motivate your patients to engage in these procedures to enhance their oral health. This is also true of block scheduling if your schedule is not busting at the seams in the first place. And make no mistake — your schedule will not be full of restorative/cosmetic procedures unless you can educate and motivate your patients properly.

If I can teach you only one pure concept in this article; if I can distill 20 years of practice into one all-encompassing philosophy; if I can communicate to you the most important strategy that I have utilized to build a multi-million dollar fee-for-service practice from scratch, it would be this: The degree of success or failure of any dental practice is influenced most strongly by the quality of the initial oral examination experience. It is what transpires when we are up close and personal with our new patients that ultimately determines our practice's level of success.

If you were to be interviewed by a television show host once a week for the next 40 years, and the result of those interviews determined your wealth, health, and day-to-day professional fulfillment, when would you begin preparing for those interviews? Several weeks before the first interview? One day before the first interview? In the green room minutes before the first interview? Or maybe, like "Dr. Wing-it," you will see how the first few hundred interviews go and perhaps make some improvements as you go — if you feel like it on that particular day.

We do not have interviews with television hosts, but we are interviewed many times each week by our new patients, and those interviews certainly determine our success and professional fulfillment. With all of this hanging in the balance, it's imperative to understand that every time you walk into the room to meet a new patient, it's "show time." It behooves you to present yourself as exquisitely prepared, with a highly structured, effective, and well-choreographed presentation.

We have so much to gain when initial oral examinations result in positive outcomes. A positive outcome means that the patient follows through with the entire treatment plan in the most expedient time frame they can afford. Additional outcomes of an effective initial oral examination experience include the near-elimination of broken or cancelled appointments and an absence of payment and collection problems. In my practice, which includes the schedules of two hygienists, one full-time associate, three part-time specialists, and myself, we conclude most days without any cancelled or broken appointments. In my personal schedule, nearly every day is a day with no schedule deletions and occasional schedule additions such as an emergency new patient, etc. Our accounts receivable are less than one month's production. I think we would all agree that many of our disappointments in practice, including financial stress, would be resolved if (nearly) every patient accepted our treatment recommendations, followed through with treatment in an expedient fashion, presented for their appointments and paid their bills according to the office policies. That said, the initial oral exam deserves a thorough analysis, a logical structure, a systematic delivery, and a commitment from the dentist and staff to its relentless improvement. This, of course, must be combined with a highly trained staff committed to excellence in order to deliver these results. I have this great staff because I can afford to pay them handsomely ... because my patients follow through with treatment, show up, and pay promptly ... because my highly trained staff trains them to do so ... and round and round it goes. Are you getting the picture regarding the resolution of your staffing challenges?

After 20 years of continuous improvement, the following method has brought me more success and fulfillment in dentistry than I ever could have imagined. First, we must embrace Dr. L.D. Pankey's philosophy that it is our job to motivate our patients to improve their oral health. Our patients have not been to dental school, they have not treated thousands of patients, and they do not understand the morbid results of tooth loss, and, just as importantly, bone loss, as Dr. Carl Misch describes so eloquently. If we do not teach our patients this credo, then no one will, and we will only have ourselves to blame for their apathy. The skill to motivate patients is no less important than the skill necessary to prepare a tooth or develop a stable, predictable occlusal scheme. The finest dental skills cannot help any patient without the concomitant skill to motivate. In other words, our job is not complete after we have examined the oral cavity and described a treatment plan. We must also motivate! Some dentists feel that their obligation to motivating the patient ends after they have matter-of-factly described a single procedure or single treatment plan developed without any patient input. If the patient follows through with treatment, great. If not, then so be it. For those dentists who embrace a "You can lead a horse to water but you can't make him drink" philosophy, they will never reach their true potential as healers. And their patients will not reach their true potential for oral health, either.

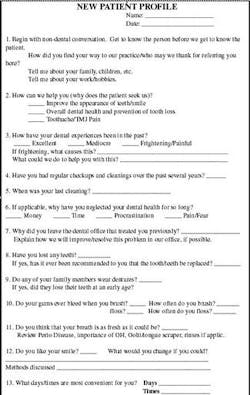

Secondly, we must gather all pertinent information about the patient in a thorough, systematic fashion that is also time efficient. I have gone so far as to develop my own customized patient orientation and examination forms specifically for this purpose. These forms have undergone more than 15 years of continuous improvement. The first form that I complete with every new patient is our Patient Profile form. It consists of 13 questions designed solely to help me understand the history, needs, and desires of the patient. I want to know what interests my patients, and I want to know it as early in the new-patient experience as possible. This will determine how I present my findings and treatment recommendations at the end of the initial examination. It will not, in most cases, determine the treatment plan — only the way I will present it. This allows me to be much more attentive to the patient's needs and desires. For example, if a patient informs me that what she needs most is to be able to masticate comfortably on her posterior teeth, I am not going to include the fabrication of eight anterior porcelain veneers in my presentation. I will mention this option later, if appropriate to her case, after I have restored her posterior function and support as she requested. The completion of this form also requires a discussion of how apprehensive the patient may be. If the patient is fearful, I want to know precisely why.

When you engage patients in these types of questions, their answers may surprise you. You will likely find that their fears and apprehensions are easily managed with some very simple procedural enhancements on your part. They may only need the sound of the hand piece drowned out, or they may need Valium. Regardless of the problem and the solution, at this point I know I have impressed upon them that I have actually listened to them and will deliver exactly what they desire. This alone can mitigate much of the apprehension our patients experience. Furthermore, it is much easier at this point to educate them on new modalities for cosmetics. I believe, like Dr. Joe Steven, that dentists complete more aesthetic procedures by having a large pool of happy, calm, "regular patients" who at some time in their lives decide they want to improve their appearance. When that day comes, if I have done everything right, they will come to me. Just for your information, I do very few veneers. Bleaching, adult orthodontics, implants, full-mouth reconstructions? We do a ton of those!

The next custom, relentlessly improved form that I complete is the Medical History/Charting/Treatment Plan form. This form, when completed, provides all of the raw data needed to diagnose and plan treatment; continually monitor treatment completed and treatment yet unfinished, and fulfill all medico-legal requirements. These forms are filled out in a highly systematic fashion utilizing clinical and radiographic observations such as oral cancer screening, occlusal relationships, periodontal status, etc. New staff members easily understand these forms and as long as I complete them, I will not miss one bit of necessary information, medico-legal or otherwise. The completion of this form marks the end of the raw data-gathering phase.

Next, it's on to the data processing phase! We must now formulate a treatment plan or various treatment choices and command a thorough understanding of their advantages and disadvantages. I would suggest that you do not utter a word to your patient about your findings or your treatment plans until you have complete command of these points. If the case is too complex to determine various treatment plans on the spot, then by all means take diagnostic casts and mount them on an articulator. This is an absolutely mandatory protocol if the vertical dimension or anterior guidance must be altered. Study these casts thoroughly, develop several plausible treatment plans of varying costs, and review them with your patient at a subsequent consultation appointment. My default mode is to develop the most "ideal" treatment plan that I can provide first and alternative treatment plans subsequent to that, regardless of the patient's financial condition or even their input during the completion of the orientation form. Remember, I am only developing treatment plans. The way that I present these plans will be determined by the patient's input provided on the orientation form. I find that the vast majority of my patients proceed with "ideal" care over a time period they can afford. Also, by proceeding in this way, I will never "under-plan" a patient who can afford the best that dentistry has to offer.

Once the treatment plan(s) have been developed, it is time for the most important phase: the discussion with the patient regarding his or her condition, my recommendations, and expectations. If "show time" began when I presented myself to my new patient, then the articulation of my findings, observations, and treatment plan(s) is the climactic act. I remember during my first several months in practice, I had such confidence in my diagnostic and treatment planning skills that I would provide an absolutely ideal treatment plan to every new patient without any regard whatsoever for their needs, desires, and financial limitations. I can now look back on those presentations as the cataclysmic act.

We have now reached the moment of truth. This is the point where many dentists pause, swallow hard, and proceed with their explanations and recommendations and say a "Hail Mary" that the patient will accept treatment. It doesn't have to be that way. At this point in the new-patient experience, I know that I am going to deliver a presentation that will not only educate the patient, but also make him or her actually enthusiastic about proceeding. I know this without any doubt whatsoever and this is reinforced to me every single day of practice in my office. This confidence can only come about when my presentation is crafted to fit the patient's needs, desires, previous dental history, and previous dental "baggage" in mind. By verbally reviewing the New Patient Profile form and recording the patient's responses, it is very easy for me to consistently obtain this vital information. Then, it is simply a matter of telling them what they need in a way that satisfies those wants. To provide further credibility to my presentation and further enthusiasm and motivation to my patient, I take four photographs on one screen with my intraoral camera. Then, I print the photograph, mount it in a Kisco® "Photo Analysis" card and fill out the card with practical, nontechnical descriptions of my findings and recommendations. I make a copy for the record and give the original to the patient. It is quite likely that this very professional and extremely impressive piece will live on for several weeks and several discussions with the patient's spouse and/or loved ones in order to arrive at the correct decision to proceed with treatment as I recommended.

I always end the appointment by asking this question in precisely this way: "Is there anything that I failed to discuss or anything that I did not discuss adequately?" I do not ask, "Is there anything that you did not understand?" This question is much different than the first one. People resent any implication that they cannot understand our descriptions and recommendations. This is a way to place the burden of their understanding on me rather than on them; consequently, it provides a much more comfortable environment for patients to open a discussion about their concerns, if any.

In our practice, every single examination on every adult patient is done precisely in this fashion — without exception. These examination protocols are highly systematic, and, as such, are highly predictable in their outcome as well as with their time requirements. Early in my practice, I noticed that some examinations took only 10 to 20 minutes and others took much more than one hour. Furthermore, the time spent (wasted) on long examinations was not at all proportional to the complexity of the case or the amount of information gathered. The time spent was only proportional to the complexity of the patient's psyche! Can you imagine the difficulty I had trying to stay on time throughout the day? Currently, I book 90 minutes for a new patient with me, not the hygienist, not ever. This gives us time to expose and mount a full-mouth series of radiographs, complete the New Patient Profile form while the films are being developed and mounted, gather my medical/dental/clinical information, review my findings and recommendations verbally with the patient, take the intraoral photographs and mount them, fill out the Kisco® card, review it with the patient, answer any questions, and then bid them farewell. With a highly systematic, well-scripted, and well-choreographed initial oral examination experience, I know the routine, I know the time requirements, and, most importantly, I know the outcome!

As I personally escort patients to the front desk, I always inform them that they may develop some questions for me after they leave and if so, to please call me at my office at any time. I part by saying "_______, it was a pleasure meeting you, and Kathy or Ginny will take care of you from here." When the patient arrives at the front desk for check-out, one of my patient coordinators will, perfectly on cue, ask how the examination went. The patient accolades are, as you can expect by now, absolutely predictable: "That was the most thorough, pleasant dental examination that I have ever had." I know the answer to my patient coordinator's question before she even asks it. A systematic process will always result in a predictable outcome.

At this point only one barrier to treatment remains. You guessed it — money. The more payment options you can offer the patient that do not put the practice in any jeopardy, the better. We offer an outside financing company (Wells Fargo) option with six months of 0 percent interest, and we take all major credit cards; we never offer in-office financing. Payment is due at the time of service. Anyone who is unable or unwilling to commit to these parameters is not appropriate for our practice.

It's very rare, but should this be the case, and I have the understanding that my patient's situation and needs are dire, I or my associate will simply proceed with treatment on that patient at no charge. I find it infinitely more satisfying to choose my charity cases at this time, rather than after I have completed treatment, only to be faced with a delinquent account. I am happy that my protocols allow me the profitability to do this without any encumbrances for certain patients in need.

You may have gathered that my methods concerning the initial oral exam may seem dogmatic and contradict the advice of many practice-management gurus. I believe strongly that introducing a patient to a practice via a hygiene visit is logically flawed and wastes tremendous amounts of our and the patient's valuable time. Why schedule a generic cleaning when you do not have any understanding about the patient's periodontal condition? You may be planning for a generic scaling and prophylaxis when the patient actually needs scaling and root planing with local anesthesia. This is a waste of time, money, or insurance benefits for the patient. What if the patient has a bleeding disorder, a heart murmur, a prosthetic joint, or has had an MI within the last six months? Do you routinely review these points on the telephone with every potential new patient? Not likely! All of these conditions require sending the now-frustrated patient home without the cleaning that he or she expected. What a way to get off on the wrong foot with a new patient!

By examining the patient first, I have the opportunity to evaluate the patient's medical history and determine the appropriate hygiene procedure. In my experience, those patients who have "sneaked through" the normal channels and secured a hygiene appointment at the first visit usually become patients who are stuck on the hygiene wheel, rarely follow through with treatment, are unreliable about appointments, and use desirable hygiene time that would be better used by other patients who are undergoing active dental treatment. These are the hallmarks of a patient uneducated and unmotivated by their dentist. Lastly, these patients are very resistant to making an appointment for the proper initial oral examination once you have satisfied their need for a "cleaning."

You may also feel that I devote an inordinate amount of time to new patients. Even though I have devoted one and one half hours to the initial examination, I easily make up this time many times over. A properly educated and motivated patient elects a higher quality treatment plan, moves through treatment expeditiously and without the impediments of broken or cancelled appointments, unfulfilled payment obligations, and the time it takes to re-educate, re-motivate and re-answer questions at every appointment. Furthermore, and most importantly, when the dentist does not examine the patient first, he or she forfeits so many of the opportunities that allow us to be successful listeners, educators, motivators, and thus, healers.

Invest time developing, relentlessly improving, and systematically executing a well-structured initial oral examination experience for every one of your new patients, and you will be on the real path, the straight path to practice success and fulfillment.

... If there is anything that I failed to discuss, or did not discuss adequately, please do not hesitate to contact me ...