Revised Second Version – January 2015 [1]

In 1975, together with my two colleagues at the University of Kent at Canterbury in England, Peter Bird and Graeme Macdonald, we published a monograph entitled: Statements of Objectives and Standard Practice in Financial Reporting. It was published by Accountancy Age Press (London) and was favorably reviewed in the learned academic journals and professional trade magazines in the world of accountancy at the time. The monograph also played a small part in motivating the movement already gaining momentum of standardizing the financial reporting of organizations as to key definitional terms such as current versus fixed assets, current versus long-term liabilities, revenues, cost of goods or services sold, gross profit, direct variable and administrative operating costs, earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA), free cash flow, and net income.

Since 1973, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) have been the organizations of choice in the private sector for establishing standards of financial accounting that govern the preparation of financial reports by non-governmental entities. Those standards are officially recognized as authoritative by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) [Financial Reporting Release No. 1, Section 101, and reaffirmed in its April 2003 Policy Statement] and both the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants [Rule 203, Rules of Professional Conduct, as amended May 1973 and May 1979], and the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England & Wales with the European Community and other countries versions of same. [2]

Such standards are important to the efficient functioning of the economy because decisions about the allocation of resources rely heavily on credible, concise, and understandable financial information. In America, the SEC has statutory authority to establish financial accounting and

reporting standards for publicly held companies under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Throughout its history, however, the Commission’s policy has been to rely on the private sector for this function to the extent that the private sector demonstrates ability to fulfill the responsibility in the public interest.[3]

Given this long tenure towards standardization in financial reporting of a diverse set of different entities in a vast number of various kinds of businesses in countries from around the world, this article asks and sets sail to answer the following two related “why” and one “how” questions about the American dental industry:

1. Why is there an absolute lack of standardization in accounting for dental practices?

2. Why is it that no two dental practices are accounted for alike?

3. How can we go about standardizing the financial reporting of dental practices?

Sadly, the answers to questions #1 and #2 lead only in the direction of the troubled and inconsistent handling of dental practice economic events by the bookkeepers and accounting professionals, whether CPA certified or not, who have heretofore served as attendants to the accountancy of dental statements of financial position (balance sheet) and statements of income (profit and loss).

The CPA profession, wary of liability, provides financial statements prepared by dental practitioners or their bookkeepers, and are happy to disclose that they have merely taken the accounting data as provided to them and converted this data into an acceptable financial statement compilation. If there are any errors in the presentation of data, this responsibility belongs to the dental practitioner alone, not the CPA firm.

Unfortunately, neither the accounting data as generated from one of several software accounting and dental practice management systems in use by dental practitioners – the most popular for accounting being QuickBooks and the two most popular for dental practice management being Eagle Soft and Dentrix -- , nor the financial statements as presented by CPA’s have any formal disclosures representing the data and its depiction in a financial format of a true and fair view of the economic events of the year. The width and variety of format presentation has led to absolute confusion and disparity in comparing one practice with another. There is no uniformity of what to call “Gross Profit” because there is no uniformity as to what comprises “Cost of Goods or Services Sold” (COGSS). I have seen a dental practice financial statement that discloses only “Dental Supplies” as its one line-item COGSS, and other dental practice financial statements that separate payroll of staff and associates from the pay to the owner who is often responsible for the majority of the revenue production. If “Gross Profit” is calculated as wildly as this between different practices, how on earth can “EBITDA” or “Net Income” mean anything, or resemble anything that accurately conveys the maximum amount an owner can consume in the accounting year without being worse off than he or she was in the prior accounting year.[4]

Other healthcare providers who have audits performed in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) must follow certain prescribed guidance as stipulated in underlying accounting standards. For example, the AICPA has various industry specific guides, including The AICPA Health Care Entities Audit & Accounting Guide, which are used by the industry and the accounting profession to facilitate consistency in accounting, auditing, and financial reporting.

In examining a dental practice, I have always had to recalibrate the financial statements as presented into something akin to a FASB-like report, supported by internal and chart review audits, and confirmed in several days of reconciling the dental practice internal controls or lack thereof with verifiability of the accounting records. I always recommend that patient charts be kept in numerical and not alphabetical order so that a random number generator can be used to sample and confirm the coordination of treatment plan with actual treatment with billing and collection all dated and cross verified. Should an inordinate length of time lapse between any of these four recognition points, and especially between treatment and collection, a red flag for management controls is immediately called for. The reason for the random sampling is to identify the audit procedure with a representative population that helps to eliminate bias and conforms to the mathematical theorems which justify the statistical testing procedures used as the backbone of the audit task.

I am not alone in having to do a recalibration. At breakfast with the President of Heartland Dental Care during the ADA Conference in San Francisco in October 2012, Pat Bauer conceded to me that his people have to work hard to recalibrate the financial statements of practices it is considering for acquisition. With over 565 affiliated dental offices in 26 states, Heartland Dental swings considerable weight in the method and manner of interpreting the creditability and worth of the financial statements prepared for and by owners of dental practices nationwide.

Heartland is also not alone in having to do recalibrations. This same avenue of work was confirmed by Dr. Craig Abramowitz of North-East Dental Management (NEDM) Company in its affiliation with Sentinel Capital Partners in a meeting with him and his underwriting agent, Steven Jones, at their offices in Paramus, New Jersey in June 2014. Dr. Abramowitz informed me and my principal that NEDM have been looking at acquisition packages for years and usually spend days if not weeks reconciling them into workable documents for underwriting purposes. The acquisition package they receive from dental practices range from assorted boxes of printed receipts and collection of hand-written bills and invoices to non-reconciled Quick Books without any adjustment for or indication of EBITDA, the key financial metric NEDM employs in buy-sell decision-making. Holding up the sales solicitation package I had prepared for NEDM for the sale of a set of practices in upstate New York, Dr. Abramowitz happily disclosed that none of this would be necessary. It was his opinion that my work product was the best solicitation package for an acquisition he had ever seen. In other words, it contained all the necessary material and in a preferred format for NEDM to take an informed opinion on the suitability of the acquisition. A bond between your author and Dr. Abramowitz was immediately formed.

This matter of deficient financial information doesn’t rise to and stop at only Presidents of dental practice management (DPM) companies or dental service organizations (DSO), nor only on the topic of a recalibration for the price and valuation of dental practices. It stretches to the very core of the data processing in a dental office. Jill Nesbitt, a group practice dental consultant from Tennessee, who was an office manager for ten years for a large group practice in central Ohio, wrote this to me in her reaction of the manner the accounting is executed by bookkeeping staff in the dental industry:

“I have yet to work with a dental practice that understands their dental software deeply enough to have their adjustments set up properly. No one seems to understand which adjustments need to be set up as assigned to production or collection, and these can substantially change a dentist’s performance. In addition, the dental accountant bookkeepers do not realize that they will get different numbers for production and collection, depending up on which reports they run.”

Recently, I prepared a valuation report for adding a fourth partner to an existing three-member partnership for a dental group in New England. Take a look at the difference in three years (2011-2013) between the total sales disclosed on the group’s income statement (by the CPA) with the revenue production generated from Dentrix software.

Ms. Nesbitt again: “I have yet to find a dental practice that has adjustments set up properly in the dental software. Almost all are left to the ‘factory settings’ which are misleading. When the adjustments are improperly assigned as collection instead of production, the collection % looks terrible and the dentist may blame the front desk team for poor performance, when in fact the production is much lower than advertised and the collection % is doing well. The next major issue is when bonuses for clinical staff are based on production – especially hygienists – if the gross production number is used, then the clinical staff are hitting bonuses when in reality, the dentist doesn’t have nearly this amount of money coming in the door. If the office manager enters insurance payments (as in almost 100% of solo practices), she sees how inflated the hygienist production is because she personally enters the insurance withhold on every patient’s account. This causes resentment among the staff as well.”

An Eagle Soft illustration I became aware of arose from an internal audit performed for a large Medicaid practice where the billings and collections department failed to push one button on the keyboard which would have changed the Eagle Soft software program from aging Medicaid accounts to aging private pay. The consequence of this oversight was $300,000 of unpaid private pay bills which were never sent out for collections. In fact, other than in the clinic, there was no record of the procedures being performed much less billed. It took another year to capture the revenue streams lost because of this error. The result was a request from me to the CPA to write a one-time exception letter so that I could balance and return the income from a prior year to where it belonged and not exaggerate the income from the present year with a “windfall” collection.

The need for recalibration of the financial statements in the dental industry is obvious: Who could make sense of financial statements that masquerade profit and loss salaries as balance sheet draws; who have no schedule of accounts for actual economic depreciation as opposed to depreciation for tax purposes; and, worse, have a statement of income that can swing from a positive which on interrogation ought to be negative and a negative which on interrogation ought to be positive.

Financial reporting in American dentistry is about the worst and most unreliable record keeping my sorry eyes have seen in over forty years of auditing company accounts since my start as a faculty resident and intern in the London office of Arthur Andersen & Co. in 1972. The accounts and stories of how I am repeatedly stung by the poor accountancy in dentistry are numerous, but I select three.

The first is from a three-person dental partnership in an Eastern seaboard State who believed themselves in the solid situation of carrying $900,000 of profit in last year’s operations. I noted that there were no COGSS for their work which comprised 90% of the revenues of the practices – they had four. I also noted that on the balance sheet they took equity draws to pay themselves $400,000 each. There is no such thing as an equity draw unless you have equity – here it was growing rapidly in a negative direction --, so that when I transferred $1.2M from the balance sheet into COGSS, the $900,000 profit became a $300,000 loss. The partners were not happy with my reasoning. Bad accounting had lulled them into an irrational belief that you could still have Net Income even though you paid yourself more than your Net Income. All that was happening with these practices was a drawdown of the capital base on which the income was based to the tune of $300,000 a year. If we conceded the four practices were worth $4M, the consolidated practices would be out of business in about thirteen years. The partners were currently in their seventh year, so they had another six to go before they realized their practices were worthless but for the liquidation of their equipment and other assets, and some real estate. As a business, in another six years, the four practices would be kaput.

The second example has to do with my checking the chart of accounts of a new client-dentist that asked me to look at his operation in New Hampshire. I noticed a liability line item in the chart of accounts at year-end 2007 for $150,000. When I took my eyes over to the next year, 2008, I noticed the opening balance for this line item was $0. I inquired of the CPA as to what magnificent or magical event transpired that removed a $150,000 liability from year-end 2007 to year-beginning 2008. The CPA’s answer was: “The doctor must have made a mistake. We don’t correct mistakes. Our only task is to take his Quick Books and present it in a conventional financial statement format.”

“But you are a CPA?” I responded. “You know that a year-end balance carries forward to become the opening balance of the next year.” “Maybe the doctor doesn’t know this, but you do.”

“You don’t understand,” the CPA corrected me. “The moment we touch on the correctness of the bookkeeping, we transfer our professional position from a mere purveyor of financial statements to a certified public accountant. We don’t want this liability. That’s why we give no opinion on the accuracy of the financial statements we prepare.”

“So, basically,” I reasoned through our conversation, “the financial statements are as useful or worthless as the accounting performed by the dental practice, and your only service is to prepare a financial statement reflecting the usefulness or worthlessness of this data.”

“Yes.” The CPA agreed.

The third incident is a classified advertisement I saw that I have now seen repeated from State to State where I consult. The advertisement runs something like this:

Buy my building, and you can have my dental practice for free.

These practices have so run down their capital stock that the replacement cost to once again have a healthy and respectable dental practice business is so costly as to exceed the current value of the practice. Therefore, giving it away is more economical than continuing to suffer the resulting negative net income and negative business valuation of the practice. The building won’t cover the volume and extent of this negativity, so the selling dentist is more like a con man or woman trying to lure the buying dentist into giving him or her something instead of nothing. As I told one of these selling advertiser-dentists: “Why would I want your building when the business inside the building is worthless?” He had no answer.

We now come to the heart of this article – question #3:

How can we go about standardizing the financial reporting of dental practices?

The key to any standardization is:

· Acceptability of terms – defined and illustrated

· List of line items in order

· Transferring accounting data into the line items

For these three bullet points to have meaning and reliability, two sets of actions must take place at determined times in every practice every year:

1) Verifying accuracy of accounting data through chart review record keeping – an audit

and

2) Establishing internal controls and systems for generating and transferring the accounting data – through the assistance of a genuine CPA firm like McGladrey LLP, or a CPA firm that will provide a “true and fair” view opinion of the accuracy of the financial reporting.

While the cost of (1) and (2) is something a solo practitioner will not entertain, the moment your practice base grows to four or more, the inevitability of paying for this service is absolute. As an illustration, and returning to our three dental partners who paid themselves $400,000 each a year, we showed that they created only enough net income to pay themselves $300,000 each a year. We now add to this “less the cost of paying for (1) and (2).” For a four practice, $4M business, (1) and (2) will cost approximately $30,000 a year, or $10,000 per partner. The partners now take home $290,000 each a year but have generated genuine net income that is verifiable. In other words, their practices are marketable. There is no need for “buy my building, and get my practice free” ads anymore.

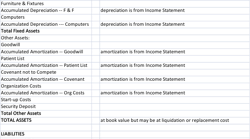

Below are my definitions of the line items comprising first the balance sheet and then the income statement or profit and loss account of dental practices. They are laid out in the same order they will be listed in the standardized financial report.[5]

BALANCE SHEET

Cash Basis

Method of bookkeeping by which Revenues and Expenditures are recorded when they are received and paid. Most dental practices have their balance sheet performed on a cash basis. This is contrasted with a transaction or accrual basis.

Date

Balance Sheets are at a point in time, usually the last day of the operating year, or at December 31st. While Balance Sheets show the estimated value in cash dollars of the investment in the dental practice, the income statement shows the operating results for the year.

Assets

An economic resource that is expected to be of benefit in the future. Probable future economic benefits obtained as a result of past transactions or events. Anything of value to which the firm has a legal claim. Any owned tangible or intangible object having economic value useful to the owner.

Current Assets

Asset that one can reasonably expect to convert into cash, sell, or consume in operations within a single operating cycle, or within a year if more than one cycle is completed each year. Depreciation is not applied to current assets.

Fixed Assets

Tangible long-term assets used in the continuing operation of a business that are unlikely to change for a long time. Depreciation is applied to fixed assets.

Other Assets

Bookkeeping items specific to dental operations such as goodwill, positive or negative, patient list, covenants, and organizational and start-up costs. This may also include investment in dental practice management software. Depreciation is applied to other assets.

Total Assets

The summation of current, fixed, and other assets. Goodwill is positive when the total assets as stated on a balance sheet are acquired for a price greater than the total assets.

Liabilities

Debts or obligations owed by one entity (Debtor) to another entity (Creditor) payable in money, goods, or services.

Current Liabilities

Obligation whose liquidation is expected to require the use of existing resources classified as current assets, or the creation of other current liabilities. In other words, those obligations probably due in the current accounting year.

Long- Term Liabilities

A debt that falls due more than one year in the future or beyond the normal operating cycle, or that is to be paid out of noncurrent assets.

Total Liabilities

The summation of the current and long-term liabilities.

Equity

The third section of a Balance Sheet, the other two being assets and liabilities. It is the

residual interest in the assets of an entity that remains after deducting the liabilities. It is also the amount of a business' total assets less total liabilities. It is usually the original capital put into the business plus the accumulated net income from the prior and current years.

This ends the list in order of Balance Sheet items as they will be standardized heretofore in the financial reporting of dental practices in the dental industry.

INCOME STATEMENT

Cash Basis

Method of bookkeeping by which Revenues and Expenditures are recorded when they are received and paid. Most dental practices have their income statement performed on a cash basis. This is contrasted with a transaction or accrual basis. I am forced to add to the cash basis, “other than for depreciation” as certain tax-savings advantages, such as the 100% free depreciation allowance supported by Congress and accepted by the IRS to motivate American companies to make large capital asset purchases, distorts the real reason and correct measure of an annual depreciation allowance. In this line item expense, the recommendation is to revert to only an accrual accounting so as to avoid a huge one-time charge distorting the net income for the present and following years.

Date

Income Statements are for a period of time, usually the operating year, or from January 1st through to December 31st. While Balance Sheets show the estimated value in cash dollars of the investment in the dental practice, the income statement shows the operating results for the year.

Income – what I prefer to call “Revenue”

Inflow of Revenue during a period of time which is broken down into cash, insurance, or Medicaid payments, and split between oral dentistry and hygiene care production.

Cost of Goods or Services Sold

Figure representing the cost of buying raw materials and producing finished goods. In a service industry such as dentistry, it is the cost of salaries, employee benefits including health insurance, laundry and uniform, and payroll taxes.[6]

Gross Income – what I prefer to call “Gross Profit”

The beginning point for the determination of income, including income from whatever sources derived.

Expense

Something spent on a specific item or for a particular purpose.

Variable Cost

Total costs that change in direct proportion to changes in productive output or any other measure of volume.

Administrative and Fixed Cost

Costs that remains constant within a defined range of activity, volume, or time period.

Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBITDA)[7]

A popular measure of cash generated from the operation of a dental practice. Financial analysts and especially those in private equity investment, frequently use EBITDA to evaluate the ability of a company to service its debt obligations. EBITDA is also used as a measure of profitability in valuing a company and in comparing a company's financial performance with other firms. Critics contend EBITDA can be a misleading financial tool, in part because companies have wide discretion in determining the dollar amount of the components used in calculating EBITDA. In addition, EBITDA does not consider the funds a company is likely to require for capital investments. Warren Buffet once famously asked: "Does management thinks the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures?” The terms “cash flow” and “free cash flow” are often used interchangeably with EBITDA. The author, like Mr. Buffet, believes in the superiority of a Net Income measurement over that of EBITDA in determining business valuation.[8]

Interest

Payment for the use or forbearance of money.

Taxes

Charge levied by a governmental unit on income, consumption, wealth, or other basis. Does not include payroll tax which is part of the cost of goods and services sold. Since most dental practices are formed as Limited Liability Companies (LLC) where the IRS treats income as “pass-through” to the individual tax return of the owner-practitioner, taxes are not applicable as a deduction from EBITDA in finding Net Income, nor is it applicable as an operating cost of a dental practice.

Depreciation

Expense allowance made for wear and tear on a fixed asset over its estimated useful life. This is not a source of funds, but an intentional allocation of practice income enabling worn-out fixed assets to be replaced when the time comes.

Amortization

Gradual and periodic reduction of any amount, such as the periodic write down of a bond premium, the cost of an intangible asset or periodic payment of mortgages or other debt.

Net Income

Excess or deficit of total revenues and gains compared with total expenses and losses for an accounting period.

Net Income Margin

Relationship of net income to gross sales in percentage form.

This ends the list in order of Income Statement items as they will be standardized heretofore in the financial reporting of dental practices in the dental industry.

In the above analysis we have successfully satisfied the first bullet point in the key to any standardization:

· Acceptability of terms – defined and illustrated

The next bullet point to be satisfied is:

· List of line items in order

This bullet point is satisfied by creating a sample Balance Sheet and sample Income Statement, laid out in terminology order, consisting of the usual assets and liabilities, and revenue and expenses items of a conventional dental practice. In addition to the format, it should be noted that although the sample financial reports are expressed in a consolidated form, each individual practice should have its results also standardized in a similar manner. I have seen dental practices show only a consolidation, thereby leaving management at a disadvantage in comparing the performances of its various practices. This is a mistake.

It is also a mistake not to have a sidebar accounting of the profitability of both the principal and the associate dentists. The methodology necessary for making this kind of assessment of dental production – the same should be done for hygiene production as well – is a work-in—progress. In an article to be co-authored with Jill Nesbitt, we expect to lay the foundation for making an analytically correct assessment of the performance and profitability of associate dentists and hygienists to the company’s overall profit. In this manner, associate dentist and hygiene leaders can direct less efficient staff to their better working methods and efficiencies.

The sample consolidated balance sheet and income statement for a sample dental practice now follow. The income statement also projects some benchmarks for each revenue and cost item, and for EBITDA and Net Income. The driver for the benchmarks is obviously revenue, but the hope is for a 20% EBITDA margin and a 15% Net Income margin. At these margins, positive multiplier on valuation will apply.[9]

Once standardized in the manner recommended, practices are now comparable with each other provided the last bullet point in the key to standardization is also satisfied:

· Transferring accounting data into the line items

This article is not the place to show how we move from accounting system software and the data it generates into the placement of this data in accordance with the terminology, description, and identification provided by the sample financial reports. Suffice to say that this activity is not mind-shattering and a capable bookkeeper ought to be able to exhibit the necessary transactional behavior to assure the accuracy and completeness of the transfer. The audit by a CPA firm and inspection of internal controls shall supplement and confirm the accuracy and thoroughness of the transfers in line with the standardization.

Once the percentages of operating and other costs to total revenues are calculated on the same basis for every dental practice, a business valuation can be derived from Net Income. Here’s how.

Business Valuation One

Since repeatable Net Income behaves identical to a conventional annuity investment or product from the insurance industry, their Perpetuity Formula captures the business Value of a dental practice with Net Income as the numerator and cost of capital as the denominator.[10]

V = NI ÷ c

Where:

o V is the value of the Dental Practice

o NI is the Net Income in the Standardized Income Statement

o c is the cost of capital

For a multi-facility of four practices each generating revenues of $1M, or $4M of consolidated total revenues, at a 15% net income margin, the net income is $600,000. This is the “NI” in the formula shown above.

Returning to the New York State Society of CPA’s terminology, we find this as the definition of:

Cost of Capital

Rate of return that a business could earn if it chose another investment with equivalent risk. It can also be thought of as a “hurdle rate” necessary for acquiring interest in a dental practice(s) from a buyer, an investor and/or lender. I shall employ the public/private equity cost of capital as it is well known the interest by private equity groups in the acquisition of dental practices.[11]

Cost of Capital might be thought of as a hypothetical concept – another example of economic theory positing an idea without any relationship with what happens in the real world – but for the foundational work of Fischer Black in the 1970’s.[12] Running right along with the standardization movement in accounting was the perceived need in finance to lend empirical credibility to the denominator of the annuity or business valuation formula.

Today, Fischer Black’s work has been ably taken over by Professor Aswath Damodaran at the Stern School of Business at New York University. This work consists of empirical data on a number of financial variables of over 6000 companies in over 100 industries.[13] Identifying the private equity industry as the line item to use delivers a January 1, 2014 cost of capital of: 9.46%. This is the “c” in the perpetuity formula above.

Putting the numerator – NI -- together with the denominator – c -- gives a business Valuation of: $600,000 ÷ 9.46% = $6,342,495.

Finally, dentistry has achieved a multiple.

A set of practices with total revenues of $4M is now valued at a multiple of 1.58. The era of dental practices being sold for less than the total collections of the prior year is over. While existing appraisal techniques value a $4M practice at between 60% to 90% of prior year collections – multiples of less than 1.0 --, or $2.4MM to $3.6MM, standardization of financial reporting as represented in this article has instead demonstrated and proven that a set of dental practices with a 15% genuine net income margin on $4MM of total revenues is valued at $6.3M.[14]

Business Valuation Two

The reader may be curious for the reason why revenues were divided between cash and insurance or private pay, and Medicaid, and why EBITDA is centrally featured as a line item in the income statement. This has to do with a method of valuation prevalent from the interest of the private equity industry in the dental industry.[15]

Wholly private pay practices are currently valued at 6 times EBITDA while wholly Medicaid ones at 3 time EBITDA. Those which have mixes are pro rated accordingly.

For example, in the table below, this method of valuation is calculated for a set of practices operating as “Main Street Dental Group” under a 100% private pay, a 50%:50% private pay to Medicaid ratio, and a 100% Medicaid.

This method of valuation would evaluate Main Street Dental Group as having a valuation between $3.6 million and $7.2 million contingent on the percentage of Medicaid that is in the revenue base of the practices.

The preference for this method of valuation is that, provided certain criteria are met the most important of which is a minimum EBITDA in the $1-3M range, it is hard to beat a market price whether you are inquiring the current price of tomatoes, Hondas, or dental practices. No other valuation method can best that. Still, the formula 6X EBITDA and 3X EBITDA can change in a New York minute. This method of valuation requires vigilance over market practices and pricing.

The Private Equity Industry and Its Cost of Capital

It is only fair to ask why despite cost of capital data on more than one hundred industries and over six thousand companies we choose to identify the prevailing denominator in the perpetuity pricing formula for dental practices as the private equity industry (Business Valuation One) or develop a pricing model predicated on the use of EBITDA as developed and executed in the private equity industry (Business Valuation Two). The answer is volume of available capital.

We know three things about dentistry and the capital markets. One, private equity has a demonstrated interest in retail dentistry; two, private equity has purchased a considerable number of practices over the years; and, three, private equity has the funds to deliver on a PSA (purchase-sales acquisition) contract and doesn’t have to go cap-in-hand to banking sources to raise capital to buy practices. Private equity groups invest in billion dollar businesses so an investment of $10-100 million to buy a group of dental practices is well within their capital wheelhouse. The same cannot be said for the other vested interest group for buying dental practices – state-licensed dentists.

The pie chart below demonstrates the capital capabilities of the two groups. The blue of private equity swamps the red of retail dentistry. For every dollar 150,000 dentists have available for acquisitions, the private equity market has $60. Private equity has an asset base of $3 trillion while the dental capital market is equivalent to the size of its 150,000 dentists operating in about 90,000 businesses each with an average capital investment of around $550,000 – a capital value of $50 billion. As the predominant capital force in the dental market, private equity and its cost of capital is the correct metric for valuation purposes.

We now come to the final and all-important section of how to assure creditability in a dental practice or group of dental practices’ financial statements. This White Paper has chronicled the failings of operating performance reports in the dental industry. To repair this too evident weakness in the believability of dental practice financial reporting, I would add to the standardization herein proposed an annual internal audit to address the internal control, data processing, and other features that directly address and lend credibility to financial reporting. In the case of dentistry, there are seven reasons why the internal audit should play an important role in the accounting for dental practices.

1. Bookkeeping in a dental practice is often performed on a daily basis by those untrained in Quick Books or comparable software accounting systems. This means those who keep the books often learn this activity either by a two-hour session with a certified public accountant (CPA) or through online courses.

2. The end result of uninformed bookkeeping allows for incorrect, unlabeled, or wrongly categorized accounting entries to generate inaccurate accounting summaries.

3. This is a phenomenon that is a regular occurrence in dental practices owing to Quick Books' inability to translate a year of record keeping into an acceptable and compiled balance sheet and income statement.

4. The usual responsibility of taking Quick Books summaries and turning them into acceptable compiled balance sheets and income statements is through the appointment of a CPA who, in executing the compilation review, operates under the limiting objective of only putting accounting information into a uniform presentation, absent notes and certainly absent any opinion of the worthiness of the financial statements being compiled.

5. An in-house internal audit introduces a third party into the bookkeeping process, enabling inaccuracy in entries, summaries, and translations to year end to be caught so that a Quick Books year-end statement is strengthened with a backdrop that has involved an examination of each of the following:

- Internal controls, including the detection of fraud and embezzlement

- Analysis of the data processing

- Random sampling of patient charts as to their accuracy and content

- Billing and collection procedures

- Other matters not to forget governmental-required record keeping in the instance of Medicaid services

6. In other words, the internal audit provides a safeguard for the compiler of the financial statement to have more faith in the accuracy of the bookkeeping.

7. More faith in the accuracy of the bookkeeping transfers to more faith in the financial statements of the dental practice by outside entities such as banks, insurance companies, and others who may have or may be thinking of having a vested interest in the future of the dental practice; also, it doesn't hurt for attracting associate dentists, either.

Loans for new acquisitions and increased credit lines for working capital, equipment, and supplies do not come from a tooth fairy but from solid and believable financial statements.

To the penny counters in the dental industry who scream: "And who pays for this internal audit or auditor?" I end with a simple conclusion about the inexpensive financial assurance of an internal audit:

The entire process takes less than three days to complete, including half a day to write the report, attach audit findings, and pen the internal audit opinion. The total cost of the internal audit is in the $2500 range.

Here is an internal audit opinion for a set of four dental practices dated August 22, 2013:

I have performed an internal audit on the accompanying statement of financial position of Main Street Dental, which included the financial statements as of December 31, 2012; June 30, 2013; and August 22, 2013, and the related statements of activities and change in net assets, functional expenses, and cash flows for the year then ended in 2012 and to mid-year of June 30, 2013, and as at the date of this opinion letter.

I took as my responsibility to express an opinion on these financial statements based on an examination of internal control with an assessment of a valid separation of operational duties within the organization, its cash and receivables, charts review, and other activities -- owner withdrawals, payroll, accounts payable -- made as part of my audit and its affect on the performance of Main Street Dental.

I conducted my audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that I plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. An audit includes examining, on a test basis, evidence supporting the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. An audit also includes assessing the accounting principles used and significant estimates made by management, as well as evaluating the overall financial statement presentation. I believe that my internal audit proves a reasonable basis for the following opinion:

"In my opinion, the financial statements and attachments referred to above represent fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of Main Street Dental as of December 31, 2012, and as of June 30, 2013, and its change in net assets and its cash flow for the year or mid-year then ended in conformity with the accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America."

If it is assurance you hope to generate in yourself as dentist-owner, as well as those interested in your business, it is advisable to spend a couple grand each year having an internal audit performed to lend substance and credibility to your financial statements.

[1] The author is a consulting economist to the dental industry and contributing writer to leading dental publications. He can be contacted at (702) 578-2757 and [email protected]

[2] The IASC became the IASB with “Board” replacing “Committee” in 2003. Original members of IASC are the accountancy bodies of Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, Mexico, the United Kingdom and Ireland including the accountancy bodies of England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, and the United States of America. Thirteen other countries have joined since 1973.

[3] From the FASB website available at: http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Page/SectionPage&cid=1176154526495.

[4] This definition of income is found in J.R. Hicks, Value and Capital, first published 1939. If you parse this definition of income correctly, you will learn the importance of repeatable net income and of depreciation as a set-aside to ensure that the capital base from which the income is earned has not shrunk from one year to the next.

[5] Thanks go out to the New York State Society of CPAs for their providing the definitions. Their definitions are available at: http://www.nysscpa.org/glossary/term/121. Italics are used for definitional terms I am adding.

[6] From a GAAP perspective and presentation, expenses such as salaries, health insurance, and payroll taxes would appear in the Income Statement under the caption of “operating expenses” and not “cost of goods or services sold.” Owing to the grand misstatement over the years of owner/partners salary expenses acting as balance sheet draws instead of operating expense, and the fact that the principal cost of providing dental service to patients is payroll to staff and associates, I am recommending this exception to otherwise GAAP-compliance in dental practice financial reporting. Certainly, this treatment standardizes what is meant by “Gross Profit.”

[7] This is my second and only other exception to GAAP. As with COGSS in healthcare accounting, EBITDA is also considered a non-GAAP measure. Here is an excerpt from SEC guidance (but applies to private entities issuing GAAP statements): “An example of a non-GAAP financial measure would be a measure of operating income that excludes one or more expense or revenue items that are identified as ‘non-recurring.’ Another example would be EBITDA, which could be calculated using elements derived from GAAP financial presentations but, in any event, is not presented in accordance with GAAP.”

[8] See Climo, Thomas, “What is your practice really worth?” July 11, 2012, DrBicuspid.com, available at: http://www.drbicuspid.com/index.aspx?sec=wom&pag=dis&ItemID=310992.

[9] To be shown in the Valuation section below. See Climo, Thomas, “The 4 Methods of Valuing Dental Practices, Parts 1, 2, and 3,” June 9, 16, and 23, 2014, DrBicuspid.com, especially note at bottom of Part 3 which reads:

“The reader is invited to change the net income and EBITDA margins in the illustration that followed analysis and valuation of practice No.5. The higher the margins move, the more likely that positive and not negative multipliers will be achieved with a valuation number outstripping prior year revenues. 6% and 12% net income and EBITDA margins are too low as indicators of performance for a positive multiplier to result. Try 15% and 20% -- the margins for net income and EBITDA I use in my White Paper -, and watch positive multipliers emerge for the valuation methods with the exception of method 1, which may reach 1.0 but no higher, and methods 4b and 4c in which Medicaid accounts for half or all of a practice's revenues.”

[10] Some readers of this valuation section may be unfamiliar with use of the abbreviated perpetuity formula used herein, being more familiar with discounted present value and its formula:

Where "C" stands for either EBITDA or net income," j" is the date of valuation, "r" is the cost of capital, and "n" is the number of years quantified. However, when "C" is the same number every year -- which is what repeatability means -- this formula mathematically reduces itself to the perpetuity formula: V = Cj ÷ r.

[11] See the McGuire Woods law firm’s analysis in “Private Equity Investing in Healthcare – 13 Hot and 4 Cold Areas,” available at: http://www.mcguirewoods.com/news-resources/publications/health_care/private-equity-investing-healthcare.pdf. Dental Practice Management is “hot area” #8, and features my article, “The Emergence of the Dental Practice Management Company,” Dental Economics, September 2009.

[12] See Perry Mehrling, Fischer Black and the Revolutionary Idea of Finance, New Jersey, 2005.

[13] The data set is available at: http://www.google.com/search?q=useful+data+sets&rlz=1C1ASUM_enUS497US497&aq=f&oq=useful+data+sets&sugexp=chrome,mod=0&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8. The research has been compiled and put in a “useful data set” format by Damodaran. Note that sometime after January 1, 2014, the Stern School data set moved from data collected by “Value Line” which had the Private Equity sector to data collected by “Cap+ IQ” which does not. To review an analysis when the Stern data set employed “Value Line,” see Climo, Thomas, “Dental Industry outlook brightens as cost of capital falls in 2014,” January 27, 2014, DrBicuspid.com, available at: http://www.drbicuspid.com/index.aspx?sec=wom&pag=dis&ItemID=315062. See also The Little Book of Valuation: How to Value A Company, Pick a Stock, and Profit by Aswath Damodaran, New Jersey, 2011.

[14] Since representing a changing and dynamic part of the securities industry, cost of capital is a movable feast, and attention to changes in the cost of capital per industry sector must be monitored and reset for each valuation date of any valuation performed.

[15] See Climo, Thomas, June 23, 2014. “The 4 Methods of Valuing Dental Practice – Part 3,” DrBicuspid.com.

[16] This section borrows heavily from two of my articles in DrBicuspid.com on October 8, 2013 and July 24, 2014. Climo, Thomas, “Internal Audit provides inexpensive financial assurance,” and “Why your dental practice should exercise an annual internal audit.”

[17] The first version of this paper benefited from the accounting insights of Stephen McClelland of McGladrey LLP, Partner Northeast Healthcare Industry Leader. He pointed out each occasion – COGSS and EBITDA – where my standardizing of the financial reporting of dental practices was an exception to GAAP-compliance for the healthcare industry. The resulting footnotes, numbers 6 and 7, are his.

In the second version, I was assisted in improving on the first through the observations, comments, and generous sharing of practice information from Jill Nesbitt. I should also like to thank all of my owner-dentists and staff with whom I am associated for having trust in me and allowing me to learn about their industry through consulting assignments.