Part 11 — Outcomes-based practice ...Factor switching for building better practices

by David W. Chambers, EdM, MBA, PhD

Pat Dallas @ FPG International

Switching factors is the most powerful of the outcomes-based dentistry techniques, because it builds on the underlying principles of dental practice.

So far, we have explored three methods for finding and fixing those parts of a dental practice that improve one procedure or another. Practices get better because of what dentists do to them, not because of what researchers or continuing-education experts know. Even general truths and universally effective methods and materials must be correctly incorporated into practices. The old phrase, "It works in my hands," (or "It doesn't work for me") has been given a new, rigorous, useful meaning.

The first two techniques presented in this series concerned themselves with components. These are the prepackaged parts of procedures that must be used in their entirety. A component is a dental material, a piece of equipment, a staff member, or anything else that is a bundle of characteristics, usually some good and some you would like to change. Factors, the other approach to analyzing procedures, are the characteristics contained in those components. Factors include ease of use, patient sensitivity, cost, and other desirable characteristics. SUVs are an example; we want factors such as size, comfort, and fuel efficiency, but we buy brand names.

There are two things we can do in outcomes-based dentistry with either components or factors. First, we can search for those components and factors that make the most impact on our practices. Second, we can switch combinations of components or factors to improve our practices. We have looked at component search, component switching, and factor search. It is now time to consider factor switching.

Switching factors to see which ones improve practice is the most powerful of the outcomes-based dentistry techniques presented so far, because it builds on the underlying principles of dental practice. It is also possible to use this approach to explore the effects of more than one factor at the same time. Consequently, the procedure is a little harder to use. Some planned manipulation of the practice is necessary, and results need to be collected in a quantifiable fashion. There is a little arithmetic involved, but it all can be done with paper and pencil.

The example I've chosen to illustrate factor switching is bonding and bonding agents. This is one of the tragedies of evidence-based dentistry. Industry hype and the reaction from the scientific community have created an impression that bonding is entirely an issue of the characteristics of one bonding material vs. another. Choosing the material that performs best in the abstract is not the same as providing the most valuable service to patients. The rules of good research have distorted the rules of good practice.

Let's assume that a practice has used factor search to explore some of the characteristics of bonding in the practice. Because the practice has been exploring good-performing and poor-performing characteristics for some time, the dentist has developed a personalized way of measuring results. On a piece of paper, he makes specific comments about ease of handling, cost, initial appearance, initial functional characteristics such as strength and form, and long-term serviceability. The dentist has a weighted scale favoring the outcomes that are most important, but this is all subjective and individual circumstances can override the scale. The dentist simply enters a number for each result from 1 to 9, where 9 means it did everything desired with no unexpected negative effects. One means this was a disaster and it probably will never be tried again.

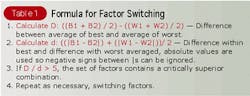

Table 1 records some of the history of factor search in this example office. Six variables seem to be involved in differentiating good results from poor ones. To perform a factor-switching project, the dentist creates a procedure composed of all the best factors and another procedure composed of all the worst. In our example, the best procedure uses a rubber dam, Brand X, a medium etching depth, desiccation of the tooth, a short curing time, and systematic placement of material. The same factors appear on the suspected worst procedure, but the values are chosen to create the worst result — no rubber dam, Brand Y, shallow etching, no desiccation, long curing times, and general placement.

It should be noted that this sort of description of the variables will never work in scientific research. What does "systematic" placement mean; how long is short? This doesn't matter in outcomes-based dentistry. Because the person who is doing the science is the same person who will use it, general terms are fine as long as they are applied consistently. One of the great advantages of outcomes-based dentistry is a recognition that personally meaningful ideas are valid even if they are not made explicit through arbitrary means.

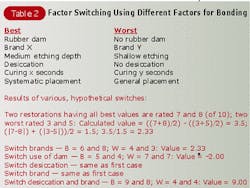

The factor-switching test involves running the stacked procedure with the best factors twice and recording the results, then running the procedure stacked with the worst factors twice and recording those results. The comparison between the two results requires a little arithmetic. The formula is shown in Table 2, but it is really much easier than it appears. The effect of running the study is the difference between the average of the best scores and the average of the worst scores. To determine if this is a big number or a small one, the result is divided by the average difference within the groups. (Remember the story about the Wisdom of Solomon who compared clay outlines of a pendant made by people who had not seen it compared to those who had seen it?) The rule for significance is very simple. If the result of the calculation is larger than 5.0, the presumed-best combination is significantly better than the presumed-worst one.

Let's run some numbers. For the data in Table 1, assume that the two best trials produce subjective scores of 7 and 8 on the dentist's 1-to-9 scale and the two worst procedures have scores of 3 and 5. The ratio of average differences between the procedures divided by average differences within them is 2.33. The dentist has yet to create a superior combination of factors since the number is less than 5.0.

Now the factor-switching procedure begins to take effect. Of the alternatives arranged in the best and worst procedure, let's assume the dentist is most uncertain about the product. Brand X and Brand Y are switched, while everything else remains the same. For the sake of illustration, let's assume that the results for the new, presumed-best approach yield 6 and 8 and the new worst approach yields 4 and 3. Having done the math, it turns out that the results are exactly the same. This would indicate that other factors in the procedures are probably what matter. Just to check this out, factor switching is done again, leaving everything the same as the first trial but switching the use of the rubber dam. Now, the results of the presumed-best approach are 5 and 4 and the presumed worst are 7 and 7. This yields a negative number. Better leave the rubber dam on!

Sometimes the factors that differentiate a successful dental procedure from a less successful one are complex. To illustrate this in the present context, assume that the dentist switches both desiccation and brand type. Now, Brand Y, medium etching depth, no desiccation, short curing, and systematic placement of the material. The results are 8 and 9 for the two trials on the best method and 4 and 4 for the two trials on the worst. The math in this case produces a value of 9.0, well above the required standard of 5.0.

This example demonstrates the power of factor switching to identify deep forces and even the interaction of multiple factors in determining the most effective procedures. In this case, the best procedure is partially a matter of the material and partially a matter of its use.

The results of a particular trial of factor switching may agree with the literature, and, in most cases, there will be some studies that support whatever dentists find works best in their practices. There will often be reports that support competing practices as well. Dentists are well-advised to go with what works best for them, based on the outcomes of appropriate studies in their own practices.