Ask Dr. Christensen

by Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD

In this monthly feature, Dr. Gordon Christensen addresses the most frequently asked questions from Dental Economics® readers. If you would like to submit a question to Dr. Christensen, please send an e-mail to [email protected].

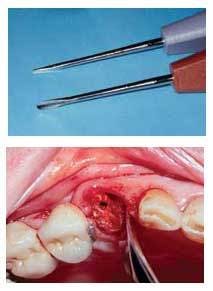

Q For years, I have been using standard surgical elevators to assist in removing teeth. Recently, a dentist friend mentioned to me that he had discovered an elevator-like instrument called a Luxator that he says works better than an elevator. How does a luxator instrument compare with a typical elevator?A Most general dentists routinely extract teeth. Estimates are that the majority of so-called “simple tooth extractions” in the U.S. are accomplished by general dentists.One of the frequently occurring frustrating challenges when extracting teeth is breaking the tooth off at the bone level, or extracting a tooth that has decayed off at the bone level. Most dentists have been taught to make a soft-tissue flap and remove bone on the facial side of such brokenoff teeth, allowing the teeth to be removed from the facial aspect. This bone removal is destructive, limits the possibility for placement of implants at a later date, and makes a permanent anatomical defect in the alveolar ridge. Also, the bone removal creates an unsightly depression when the alveolar area has healed, making esthetically acceptable restoration of the area difficult.

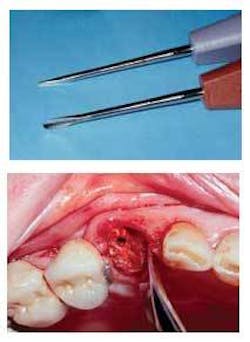

The Luxator (JS Dental Manufacturing Company) looks like an elevator, but the tip of the instrument is signifi cantly thinner and somewhat fl atter than an elevator. Luxators should be used in the following manner:

Assuming that the tooth has been broken off or is decayed at or near the bone level, the tip of the Luxator is inserted between the tooth surface and the supporting bone. The most remaining bone is usually present on the mesial or distal of a typical tooth with normal supporting bone. Occasionally, the palatal bone will be thick as well. Quite obviously, if the instrument is inserted between the tooth surface and a thin piece of bone, the bone will break when force is placed on the Luxator. Avoid this situation.

The thin instrument can be pushed apically easily between the remaining tooth root and the bone using a slight rotating movement, which compresses the bone and allows the instrument to slide farther apically. The instrument should be used slowly and gently, pushing apically, and wedging between the rigid, hard tooth surface and the bone. The result is often surprising. The tooth root occasionally pops out similar to a cork that has been wedged into a bottle. The thin facial and lingual bone usually does not break, leaving a matrix for later bone fill-in and potential implant placement.

When multi-rooted teeth have been sectioned to facilitate easier removal, and the tooth roots do not have coronal tooth structure remaining, the Luxator is used in the same manner as described previously. Because Luxators are thin instruments, the somewhat heavy force often placed on an elevator is not appropriate, as the Luxator tip will break off.

I consider the Luxator to be one of the most valuable instruments available for the situations described. It is not a replacement for elevators. It is an augmentation for relatively easy removal of broken teeth. Soon after acquiring the instruments, dentists will fi nd other uses for Luxators.

Dr. Karl Koerner and I have just completed our newest video demonstrating several commonly occurring, but frustrating, situations in oral surgery. It is V4116, “Oral Surgery in General Practice.” Among the topics demonstrated are use of the Luxators, sectioning of teeth, bone-troughing, and how to deal with numerous complications. For more information, contact Practical Clinical Courses at (800) 223-6569, or visit our Web site at www.pcc dental.com.

Q Frequently, I find that the proximal box forms on Class II, resin-based composite restorations are very deep, even to the bone level. How can I place a composite restoration in this type of situation with the expectation that the tooth will remain cariesfree?A I suggest the following technique to prevent the potential future caries problems related to the situation you described. It is not always easy, but it is one of the few methods that ensures an adequate seal and cariostatic properties in the proximal box form.