by Robert A. Ganley

Editor's Note: This article, originally titled "There Is No Standing Still," appeared in the June issue of the American College of Dentists Journal, and is reprinted with permission.

The dental industry is a delicate chain of expertise, commitment, and trust. The future will depend on how well the links work together to achieve common goals.

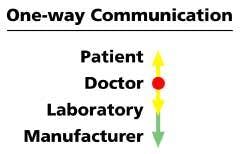

Twenty years ago, the communication and relationship between the laboratory technician and the dentist could be characterized as a one-way street — from the dentist to the lab technician. The most typical message was, "Right central crown A3," and "When is that case going to be ready?"

Lab technicians were receivers and processors of prescriptions. They made what was ordered to the best of their abilities, given the information they were provided and the time constraints they experienced.

Communication from the dental manufacturer and dealer to the laboratory was limited to product information — in other words, they gave just enough information to answer the lab technician's questions and earn the sale. Communication to the patient was even more limited. The patient asked few questions ... and the dentist asked even fewer! In fact, the patient was not intrinsically involved in the case plan or therapy decisions.

Lines of communications have changed dramatically as part of a realignment of the roles and responsibilities within the dental industry.

The one-way autocratic model depicted above was the norm for many years. In short, the flow of information emanated from the dentist to the other parties involved.

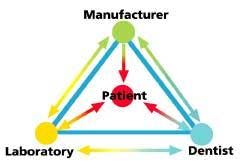

Today, the relationships between the patient, dentist, laboratory technician, and manufacturer — and, consequently, the communication that is symptomatic of the nature of the relationship — are undergoing revolutionary changes. These changes are greatly altering the direction, tone, and nature of the way each party deals with the other.

The relationship triangle

Change is exciting, and these are exciting times. We are witnessing and experiencing a revolution that is bringing the laboratory technician and the dentist closer together, and they are both moving closer to the patient.

As we examine the reasons for this change, we will discover new relationship and communication formulas for the future. From this vantage point, we are witnessing the a caring industry that is maturing and dedicated to working together to serve patient needs.

We have seen more change in dentistry in the last 10 years than we did in the previous 25. Change is all around us. We have seen changes in the products we use, the education we promote, the techniques we employ, the markets we serve, and even the industry as a whole. This change is leading to a further realignment of the roles and responsibilities of each of us participants.

What is causing this dramatic change? The convergence of these three basic conditions have become strong catalysts for change throughout the industry. These catalysts are:

- The advancement of new product technologies and techniques.

- The dentist's desire for increased financial and creative satisfaction.

- Patients becoming dental consumers and taking more control of the process.

The continuous development and release of new products is, perhaps, the most obvious and tangible change in dentistry. The introduction of dentin-bonding materials opened a new avenue of restorative dentistry. Adhesive materials provided a foundation for the expansion and introduction of restorative materials for minimally invasive dentistry. New composite resin and cementation systems have expanded indications for chairside and laboratory-fabricated restorations. Additionally, these new materials are stronger, more wear-resistant, and longer-lasting than previous materials. The new shades, translucencies, and modifiers have fortified the goal of aesthetics in dentistry.

The excitement truly arrived with the introduction of all-ceramic systems. These products provided true-to-life aesthetics never before available. The possibility of metal-free crowns and bridges captured the interest of dentists, expanding the indications for this type of dentistry and the market itself. A revolution in aesthetics and restorative dentistry was born.

However, these materials were truly of a new chemistry and required new techniques for fabrication, preparation, cementation, and bonding. The techniques the dentist used would change by necessity, and the methods followed by the laboratory technician also would need to change. This is where the first evidence of role changes became apparent.

With the development of these new products, a new partnership was required. Two-way communication, common education, and case coordination between the laboratory technician and the dentist became critical. As they stepped into these new areas of dentistry together, each learned complementary skills and began to recognize each other's value in this new equation. At first, the reason for the partnership was to avoid failure. Soon, the purpose matured to working together to achieve excellence.

The second catalyst for change in the roles and responsibilities of the laboratory technician and the dentist stems from needs growing within the dentist. More than 90 percent of dentists are sole proprietors.

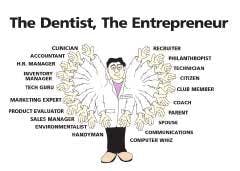

The dentist, the entrepreneur

As entrepreneurs, dentists reap the same rewards — and frustrations — of all small-business owners. Not only are they required to advance their dental knowledge and clinical skills, but they also must be accountants, human-resources managers, operations and inventory managers, technology gurus, sales and marketing experts, and more. For the most part, they bear these duties alone. Faced with this isolation, plus managed-care threats and the tedium of a "drill and fill" practice, is it any wonder that in a recent survey nearly 48 percent of dentists stated that they probably would not go into the profession if they had it to do over again. In another survey, 60 percent of dentists stated that they wanted to be working less, retired, or out of the business altogether in the next 10 years. The good news is that as products improve and shared partnerships with other dental professionals grow, more and more dentists are gaining the financial rewards and creative satisfaction they desire. This personal satisfaction, achieved through restorative work that enhances patients' self-esteem as well as their dentition, grows with each new case.

Along with personal satisfaction comes success as patient volume and case acceptance grows. The formula for success becomes clear: Combine the new materials and techniques (used in conjunction with quality, traditional materials), along with a new partnership with your laboratory technician, and communicate these options to the patient.

Successful dentists want more, and those who observe or hear about it want the opportunity to also be successful. This becomes a simple, but powerful, dynamic. Practices expand as opportunities for more restorative and aesthetic work develop. The original role of the dentist as a professional who is focused only on dental restoration and occlusion maintenance changes dramatically. As Dr. Gordon Christensen stated, "The practitioners who continue to concentrate strictly on mandatory dentistry will be left behind." Restoring smiles and patient attitudes has redefined outcomes for the patient, as well as the dentist; the dental technician's participation has become central to this success. A model has been established that promises quality dentistry, aesthetic dentistry, and patient-oriented dentistry, and is built on a foundation of the professional dental team.

The third catalyst for alteration in roles and responsibilities is the most unexpected and the most obvious. It is unexpected by virtue of our past and obvious as a result of our experiences that point to the future. Today, as patients becomes more involved in the dental process, they will be the primary catalysts for change — as well as the primary beneficiaries of that change! This role change has been dramatic. But for this trend to be valuable, we as an industry need to be aware of the messages we are sending.

In our industry's recent past, dentists have been confronted with and encumbered by the patient's perception of dentistry. Until recently, dentistry has failed to build public awareness of the success and ease of its routine procedures beyond the "fix it; it hurts" mentality. This has occurred because of the industry's aversion to self-promotion, leaving us with a patchwork quilt of independent messages and hampering our ability to create future value in the minds of consumers. It is clear that dentistry provides services that everyone needs, yet more than half of the population utilizes dental services only under duress.

The degree of reluctance to visit the dentist was a direct consequence of the degree of discomfort experienced during the patient's last dental visit where the only tangible outcome was the elimination of pain. Today, however, the outcome can be dramatically different. Frequently, patients leave the dental office with a new view of dentistry, such as the clear benefits to appearance, self-esteem, as well as function, creating a reward worth the cost. An informational and educational dynamic is taking place that is changing dentistry by changing the patient. Patients are becoming consumers, and, from now on, the rules of consumerism will apply.

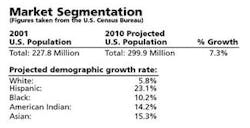

To understand these rules and their consequences, let's look at a few interesting facts concerning changing consumer demographics and attitudes. Between now and 2010, the U.S. population will increase to nearly 300 million people. Asians and Hispanics will be the fastest growing groups, each reaching a growth rate of more than 23 percent. The boomers will be retiring and the Generation X'ers will be reaching middle age. By 2020, more than 200,000 people in America will be over the age of 100. Also by 2020, 20 percent of the population will be over 65, and, with the growth of Latinos and Asians, there will be no ethnic majority.

Each of these various demographic groups tend to use dental services differently. Communicating the value of dentistry to this wide spectrum of consumers will require a highly integrated approach from all members of the dental community.

In addition to demographic changes, attitude changes also are evident in the rise of a new type of consumer. This new consumer is substantially more demanding and more engaged in the decision-making process.

These new consumers are better educated. By 2005, more than half of the population will have the equivalent of one year of college. This is an important point, because people with some college experience are twice as likely to seek dental care as those who have not attended college.

These new consumers will be wired, with more than half of the population owning a computer with Internet access. In fact, of those who are currently online, nearly 70 percent have searched the Internet for health-related information in the past year.

These new consumers will have the ability to get what they want. By 2005, almost 50 percent of the population will have a family income of at least $53,000. Higher incomes traditionally have meant higher use of dental services.

Characteristics of the "new consumer"

As the percentage of educated, technically savvy consumers grows, they will demand a more active role in the selection of products that are used and the treatment they receive.

We are an industry of only about one million people, less than half of one percent of the United States population. The size of our industry in dollars is only about $60 billion or about half the size of General Electric. We receive less than 5 percent of the total health-care expenditures in the U.S. Ours is a somewhat modest industry, but an important one. It is an industry whose main goal should be to serve its patients. As the roles and responsibilities within the industry change, we must remember that along with the great opportunities that come with change, there also is great responsibility.

A delicate chain

Our industry is a delicate chain of trust, from researchers ... to educators ... to manufacturers ... to dealers ... to laboratories ... to dentists ... to patients. And, like all chains, we are only as strong as our weakest link. So, as change occurs, we must continue to build on and support the fundamentals that always have been a part of dentistry — education, quality-tested products, and a genuine concern for the health and well-being of our patients.

Change is happening. We will either move forward or backward; there is no standing still. The future will depend on how well we come together, alter, and mature our roles; respect and rely on each other's individual strengths; and work toward our common goals.