By Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD

Q I've been using lithium disilicate crowns frequently for the past several months. Recently, I had to cut off a bonded resin cemented restoration. The removal procedure required several minutes, several burs, and I could not tell where the tooth structure began and the bonded restoration ended.

Should these restorations be bonded or cemented (luted) into place? I'm confused after removing the bonded crown and finding it extremely difficult. Also, I felt that removing the bonded restoration was observably traumatic for the tooth.

AYou're not the only one who's confused! Your question is currently one of the most asked questions that we receive at Clinicians Report. Apparently many dentists are confused and have difficulty removing bonded zirconia or lithium disilicate restorations. In my answer, I'll suggest some situations in which bonding of full-zirconia, zirconia-based, and lithium disilicate restorations is desirable, and some situations in which bonding is probably negative.

When almost all tooth-colored restorations were porcelain-fused-to-metal, removal was relatively simple (Fig. 1). A slot was easily cut in the crown, and a screwdriver-shaped instrument was placed in the slot. With minimal rotation force on the instrument, the crown usually separated from the tooth preparation, leaving some cement on both the restoration and the tooth preparation.

That simple procedure applied to zirconia or lithium disilicate restorations is only minimally successful. Research at Clinicians Report (July 2012, Vol. 5 Issue 7) shows that several diamond instruments are required to remove even one crown. Significant time is necessary for removal, and the underlying tooth is often mutilated when the restoration is removed (Fig. 2).

Full-zirconia or zirconia-based restorations

Are full-zirconia or zirconia-based crowns failing by separating from tooth structure during service? The Clinicians Report in-depth research division, TRAC, administered by Dr. Rella Christensen, has a study now in its eighth clinical year that sheds light on this subject. The study includes about 900 units of zirconia-based three- and four-unit FPDs. All of them were cemented with resin-modified glass ionomer (3M RelyX Luting Cement). To date, none of the restorations have separated from the tooth preparations. It is evident from this study that bonding of zirconia-based restorations is not necessary. This data could easily be extrapolated to full-zirconia restorations, since the only difference between full-zirconia and zirconia-based restorations is that the zirconia-based restorations have a layer of fired or pressed ceramic on the external surfaces, and this characteristic would not influence retention of the fixed prostheses.

I can conclude that unless the full-zirconia or zirconia-based restorations have inadequate mechanical retention available, they DO NOT need to be bonded, and that bonding may actually be negative when the following characteristics are considered. Resin bonding cements do not have any preventive potential, such as the fluoride contained in resin-modified glass ionomer or conventional glass ionomer cements. Additionally, bonding restorations makes them significantly more difficult to remove when necessary compared to those restorations that are cemented with resin-modified glass ionomer, conventional glass ionomer, or other older cements.

What are the characteristics of a "retentive" tooth preparation? I suggest that the tooth preparation for a full crown should have 4 mm or more of near-parallel axial walls from the gingival margin to the occlusal table, and that retentive tooth preparations should have no more than 20 degrees of lack of parallelism. Such retentive tooth preparations do not need bonding when planned for full-zirconia or zirconia-based restorations. Later, I'll discuss the few situations in which zirconia-based, full-zirconia, and lithium disilicate restorations may be better when bonded and resin cement is used.

Lithium disilicate restorations (IPS e.max)

When considering removal difficulty, these restorations possess approximately the same negative characteristics as zirconia restorations. Additionally, their use has been primarily limited to single-tooth restorations, not requiring as much retention as needed for fixed prostheses, while both full-zirconia and zirconia-based restorations are accepted for use in multiple-tooth fixed partial dentures. Lithium disilicate restorations are often even more difficult to remove than zirconia restorations, since they beautifully match the color of the tooth, making differentiation of tooth structure from restorative material or cement almost impossible. If lithium disilicate restorations are bonded with tooth-colored resin cement, our research has shown that it is extremely difficult to differentiate the restorative material, the cement, and the tooth structure. In such cases, crown removal almost always results in inadvertently cutting into remaining tooth structure and somewhat mutilating the underlying tooth structure of the tooth preparation.

The remaining question is related to their service potential when conventional, nonbonded cements are used. Are lithium disilicate restorations strong enough to seat with resin-modified glass ionomer, conventional glass ionomer, or other nonresin cements? Numerous clinical research projects have shown that these restorations can serve adequately when cemented with conventional, nonresin cements. (See Clinicians Report October 2011, Vol. 4 Issue 10 for additional information.)

Consider the strength adequacy of seating single-unit lithium disilicate restorations with conventional nonresin cements, and the difficulty encountered in removing these restorations when they're bonded. These characteristics lead me to conclude with the same recommendations I made previously for zirconia restorations. Lithium disilicate restorations seated over RETENTIVE tooth preparations as described before can have conventional cementation (luting) instead of bonding. Conventional cements usually have relatively opaque color, which is easily discernable from the tooth preparation. This easy differentiation from tooth structure reduces or eliminates tooth preparation mutilation when restoration removal is necessary (Fig. 2).

When is bonding preferred for zirconia or lithium disilicate restorations?

Tooth preparations with minimal retention

Good examples of this challenge are short mandibular second molars. These teeth often have clinical crowns with a minimal amount of circumferential parallel tooth structure. If any tooth preparation for a zirconia or lithium disilicate restoration does not meet the recommendations for retentive tooth preparations I mentioned earlier, bonding will help retain them.

Onlays

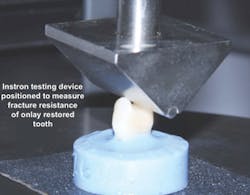

Clinicians Report recently conducted a study on the strength of onlays made from zirconia or lithium disilicate (Clinicians Report January 2012, Vol. 5 Issue 1). Fig. 3 shows the type of tooth preparation for the restorations studied. The restorations were seated with resin cement (Ivoclar Multilink Automix) because of the minimal retention of onlays when compared with full-crown tooth preparations (Fig. 4). The restorations were broken in a manner simulating the stress of occlusion (Fig. 5). All of the restorations fractured at strength levels significantly stronger than the natural uncut tooth specimens used as controls (Fig. 6). Bonding of onlays with resin cement is recommended, and this study showed the impressive strength of onlays that cover all of the tooth cusps.

Thin lithium disilicate restorations

Lithium disilicate restorations are best when made at least 1.0 mm thick. Fig. 7 shows a patient for whom lithium disilicate restorations were planned for the upper anterior teeth. The restorations had to be thin to help avoid overcontouring them. The pleasant esthetic result (Fig. 8) was achieved by keeping the lithium disilicate thin on the facial surfaces (~0.5 mm) and bonding them with tooth-colored resin cement. Conventional nonresin cements would have shown an opaque color through the relatively translucent lithium disilicate crowns. When these crowns are thin, bonded resin cement is recommended to provide optimum strength and lack of opaque conventional cement showing through the thin crowns.

Conclusion

In my opinion, based on research and clinical observations, I do not recommend routinely bonding full-zirconia or zirconia-based restorations. Use the conventional cements you've become accustomed to using for porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns. I suggest bonding only those zirconia restorations that appear to have inadequate retention.

The same conclusion can be made for lithium disilicate restorations that have adequate thickness to block the color of conventional cements and that have adequate retention. When either type of restoration has questionable retention, bonding is recommended to provide additional retention and strength.

Gordon Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD, is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah. He is the founder and director of Practical Clinical Courses, an international continuing-education organization initiated in 1981 for dental professionals. Dr. Christensen is a cofounder (with his wife, Dr. Rella Christensen) and CEO of CLINICIANS REPORT (formerly Clinical Research Associates).

In this monthly feature, Dr. Gordon Christensen addresses the most frequently asked questions from Dental Economics® readers. If you would like to submit a question to Dr. Christensen, please send an email to [email protected].

I recently made a one-hour video on all of the aspects of zirconia and lithium disilicate restorations, including tooth preparation, impressions, and cementation of zirconia and lithium disilicate restorations. The DVD, Zirconia & Lithium Disilicate Restorations – Clinical Comparison & Techniques (Item V1956), compares the materials and techniques for each type of restoration, which are significantly different. Call Practical Clinical Courses at (800) 223-6569, or visit our website at www.pccdental.com for additional information.

Past DE Issues